By Trevor Mundel, PhD

President, Global Health Division

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Introduction

Recently, a journalist asked me how much value the Global Health Division of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation places on the acquisition and analysis of robust data to measure the impact of our work. He might as well have asked how important breathing is to oxygenated blood, or eating is to a healthy diet.

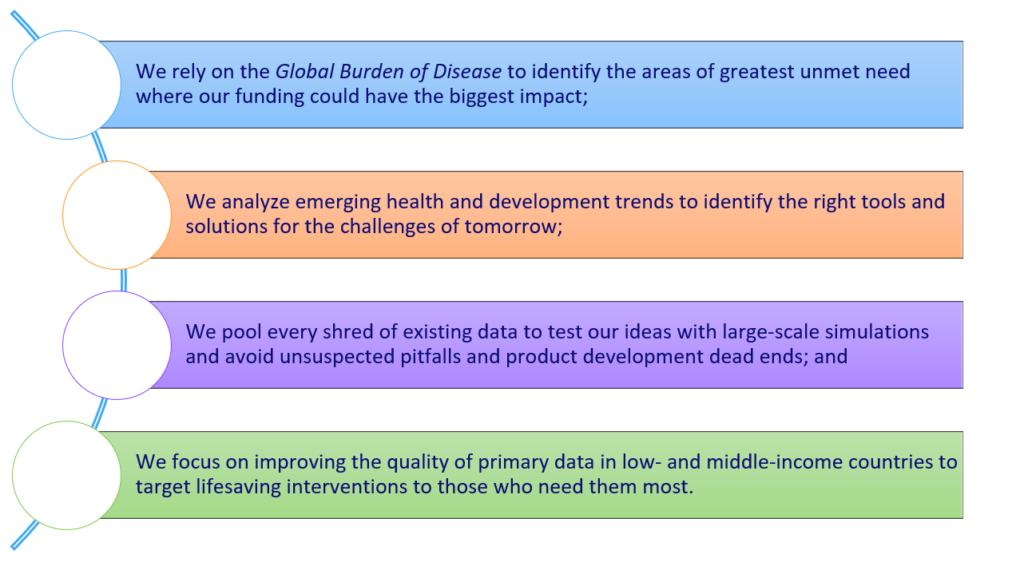

I told him that data is at the core of every decision we make:

In short, good data and smart analytics are essential to producing science that matters—science that can be measured in lives saved and disabilities averted for every dollar invested. I want to highlight two areas where the Gates Foundation is investing in data and analytics, with the goal of catalyzing transformation in global health. These examples are drawn from my LinkedIn blog series, which reflects on opportunities for innovation and collaboration in global health.

Pandemic Preparedness

Perhaps no issue demonstrates the urgent need for global collaboration more than the topic of pandemic preparedness. In October, I had the privilege of facilitating an open dialogue on pandemic preparedness at Grand Challenges in Washington, DC, with Richard Hatchett, CEO of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI); John Nkengasong, Director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Camilla Stoltenberg, Director-General of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health; and Penny Heaton, the new CEO of the Gates Medical Research Institute.

I started the session with a simple question: In the year since the formal launch of CEPI, have we made progress in preparing the world for the next pandemic? The panelists responded with a cautious and qualified “yes.”

We noted that more than 60 countries worldwide – with financial and technical support from the G7 nations and Norway – have committed to evaluating their capacity to identify a fast-moving outbreak, share critical information on the underlying pathogen and its epidemiological profile with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other national public health agencies, monitor its movement, and take action to control or mitigate the disease.

We also noted that CEPI has made amazing progress over the past 12 months in moving from an intriguing concept to an operational reality. As an organization committed to fostering the rapid development of vaccines against emerging infectious diseases – especially fast-moving, flu-like viruses with the potential to cause millions of deaths worldwide – CEPI is well on its way to supporting the development of vaccine constructs that can be advanced through early stage clinical trials and stockpiled for emergency deployment in the event of a serious outbreak.

As Richard Hatchett made clear, however, the world will not be prepared for a major flu pandemic until we have the technical capacity to identify a pathogen and produce a safe and effective vaccine in less than 12 weeks – the predicted time it would take for a virus to move from its point of origin to every corner of the world.

This means we need to move from current 20th-century approaches to vaccine development, which require years or decades of R&D, to 21st-century approaches like novel DNA- and RNA-based platforms that could dramatically accelerate development. To do so, an unprecedented commitment to collaborative science and information-sharing as well as strong funding commitments from governments and philanthropies that can de-risk important research efforts will be required.

Above all, however, we need to avoid taking our foot off the gas pedal. If we have learned anything from the world’s recent experience with SARS, MERS, Ebola, and Zika, it’s that it’s all too easy to lose our sense of urgency for innovation once a major crisis has passed. This is where continued global leadership from heads of state and the WHO remains fundamental to building the infrastructure the world needs to tackle the next great pandemic – not if, but when it occurs.

Shifting Perspectives

It’s also time—as Francis Collins of NIH has noted—for wealthy countries to shift their thinking from “donorship to ownership”—that is, from sponsoring research in Africa that is largely designed and led by expatriate scientists to fostering research that is conducted in collaboration with African scientists and African institutes of public health and medicine.

If we’re serious about preparing the world for the next pandemic, working with African governments and universities to develop strong national public health infrastructure and the real-time capacity to measure and monitor national and regional disease burdens will be paramount.

That’s why the Gates Foundation is proud to support the cultivation of African scientific talent through organizations like AESA and capacity-building initiatives like CHAMPS – the Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance Network. We’re also excited that NIH and PEPFAR have supported the launch of the Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) to foster collaboration among countries that receive PEPFAR funding to develop regional centers for medical training. These centers have the capacity to prepare 140,000 new medical workers for Africa’s health systems in the next decade.

NIH and the Wellcome Trust are also partnering on H3Africa, an amazing new initiative that is committed to mapping the links between health and heredity in Africa. The goal is for medical research to then apply the latest insights in genetic research to the development of new drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics that are designed specifically for populations living in Africa.

Open Access to Research and Data

The Gates Foundation is committed to developing transformative solutions for some of the toughest challenges in global health. We’re excited about the potential of many new products—from vaccines against the leading causes of child death, to long-acting HIV prevention methods, to novel mosquito control methods that could accelerate the eradication of malaria. But the investment that has recently generated the most excitement and enthusiasm from our Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC) is not a specific medical product.

It is the foundation’s commitment to work with the NIH, the Wellcome Trust and other major R&D funders to accelerate open access to the research we fund and the data on which that research is based. I was humbled when several members of our SAC—some of the most respected figures in medicine today—said that our collective commitment to fostering open access to published research, open data-sharing, and ultimately open research collaboration could be the single most important innovation that our organizations are remembered for a century from now.

We recently announced that the foundation’s next step toward open access publication—Gates Open Research—is officially open for business. The portal publishes articles by foundation grantees across many product development and delivery issues, which undergo transparent post-publication peer review. Gates Open Research will ultimately serve as an archive for research funded by each of our divisions:

We have made a commitment to ensuring the rapid peer review, publication, and dissemination of research that our grant-making has generated. And by requiring the publication of all supporting data, we are committed to facilitating reproducibility and transparency while enabling other researchers to reanalyze and reuse data in ways that can break down research silos, increase collaboration and efficiency, and facilitate complex meta-analyses of some of the biggest questions in health, medicine, development, and education.

Preparing for the Future

It is my hope that Gates Open Research, together with the launch of the Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute in 2018, will help forge new approaches to scientific collaboration that can overcome the challenges of a 17th-century research-sharing model and adapt that model to the urgent issues of 21st-century medicine. I also believe that open access, open data, and open science will be critical to preparing the world for the next great pandemic.

I’m excited by the quality of submissions to date, and I’m hopeful that Gates Open Research will achieve the success of Wellcome Open Research, which launched just under a year ago. Whereas it often takes six months to a year for peer-reviewed scientific results to be published in leading journals, the Wellcome publication platform has succeeded in compressing the process of publication, peer review, and indexing to PubMed to just 31 days.

Although we are making tremendous progress to reduce the leading causes of death and disability around the world, we must remain mindful that more than 10 children under the age of five continue to die from preventable causes every minute of every day. We have no time to lose, and I firmly believe we can change the world by changing the way we work together to tackle the world’s greatest health challenges. That starts with a wholly new approach to knowledge and data-sharing.

About the author

Trevor Mundel leads the foundation’s efforts to develop high-impact interventions against the leading causes of death and disability in developing countries. He manages the foundation’s disease-specific R&D investments in HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, pneumonia, enteric and diarrheal diseases and neglected tropical diseases. He also manages cross-cutting product development programs, including Discovery & Translational Sciences, Innovative Technology

Solutions, Integrated Development, and Vaccine Development & Surveillance. This work relies on close collaboration with an international network of grantees and partners.

Prior to joining the foundation in 2011, Trevor was global head of development with Novartis and previously was involved in clinical research at Pfizer and Parke-Davis.

Born and raised in South Africa, Trevor earned his bachelor’s and medical degrees from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. He also studied mathematics, logic and philosophy as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, and he earned a Ph.D. in mathematics at the University of Chicago.