By Mary P. Nix, MS, PMP Health Scientist Administrator Staff Lead for National Guidelines Clearinghouse and National Quality Measures Clearinghouse Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Like many in the clinical practice guideline community, the team working on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ’s) National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), www.guideline.gov, devoured the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) report on trustworthy guidelines when it was released in 2011[i]. For years leading up to the report, NGC and AHRQ staff and leaders had been hearing that there were too many guidelines of varying quality in NGC. In fact, others had been hearing this also and, in 2008, the U.S. Congress requested that the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) contract with the IOM to identify "the best methods used in developing clinical practice guidelines in order to ensure that organizations developing such guidelines have information on approaches that are objective, scientifically valid, and consistent."[ii] AHRQ funded the IOM contract.

The IOM guideline report and its sister report on the standards of systematic reviews launched a sequence of steps AHRQ and the NGC team have taken to support dissemination of evidence-based guidelines developed in response to the IOM report.

One of those steps involved adopting the 2011 IOM revised definition of a clinical practice guideline and revamping the criteria for inclusion of guidelines that met the definition. Analysis, input, prototyping, vetting and refining the inclusion criteria were key activities leading up to the announcement of NGC’s revised criteria in June 2013 and decision to begin implementing the criteria in June 2014.

The major change in the inclusion criteria centered on the evidence-basis underpinning the clinical practice guidelines; specifically, that guidelines are based on a systematic evidence review. While the original 1997 inclusion criteria had a criterion related to systematic reviews, the 2013 (revised) criterion provided greater specificity that clarified expectations about the systematic reviews used in the development of the guidelines. See related text box.

| NGC’s Evidence (Systematic Review) Criterion: The clinical practice guideline is based on a systematic review of evidence as demonstrated by documentation of each of the following features in the clinical practice guideline or its supporting documents.

NB: A guideline is not excluded from NGC if a systematic review was conducted that identifies specific gaps in the evidence base for some of the guideline's recommendations. |

The 2013 inclusion criteria also included a new criterion regarding assessing benefits and harms of recommended and alternative care options. For those familiar with robust systematic review methodology and reporting, this criterion is logical and consistent with the purpose of systematic evidence reviews. For those less familiar, systematic reviews find, assess, synthesize, and interpret the evidence of care options (e.g., treatment interventions) looking at benefits and harms of those options to answer specific clinical care questions.

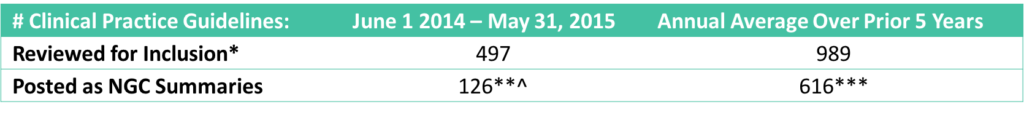

It’s now one year post-NGC-implementation of the 2013 (revised) inclusion criteria and a perfect opportunity to comment on what a difference one year makes. Take a look:

* These are guidelines reviewed against the inclusion criteria and includes both guidelines submitted by developers and guidelines identified by the NGC team

** These are guidelines that met the 2013 inclusion criteria, where the team received copyright permission, and for which an NGC summary was prepared, reviewed and posted to guideline.gov.

*** These are guidelines that met the 1997 inclusion criteria met, where the team received copyright permission, and for which an NGC Summary was prepared, reviewed and posted to guideline.gov.

^Not all guidelines meeting criteria in this time period, have been posted to the NGC site, especially those submitted recently

[i] Institute of Medicine. Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editor(s). Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011.

[ii] Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act, Public Law 110-275, 110th Cong. (July 15, 2008).