By Tom Sullivan

Editor-in-Chief of Healthcare IT News

Director of Content Development, HIMSS Media

Introduction

I went into the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society 2019 conference (HIMSS19) last month all hopped up to see a fresh range of emerging technologies: artificial intelligence, blockchain, cloud services, as well as apps and devices that collectively promise to enable the next generation of precision and personalized medicine en route to the future state of scientific or evidence-based health and wellness.

Allow me, please, to disclose that I work for Healthcare IT News, a HIMSS Media publication, so I am part of HIMSS.

Back to the main narrative: innovation was everywhere. And the most discussed topic was also perhaps the highest hurdle to forward progress. Information exchange/interoperability/data sharing is currently health IT’s hardest problem and the most pressing one, because until information can be moved around and used, until data as a raw material can be transformed into information that is a strategic asset, the full potential of all these emerging technologies simply cannot be fulfilled.

That’s a persistent thread throughout the industry, of course. But this year the feeling was different: beyond just having the industry digitized with the most prevalent three letter acronym in information and technology circles (EHR), the stage has been truly been set for digital health.

I’ve since spoken with quite a few people, including long-time industry veterans who have been working on the problem for years, if not decades, and they volunteered a similar sentiment. Now, that’s not to say by HIMSS20 interoperability will be solved, everyone will have all the data access in the world, and the gnarly practice of information blocking will be eradicated. They will not.

Instead, the takeaway is that this is starting to take shape as a problem we can actually solve -- interoperability, in fact, has been accomplished before. I lived through it in a previous job.

Let’s take a look back at history.

Web services standards

In June of 2000, I went to an event on Microsoft’s campus in Redmond, Washington, much of which has stayed with me to this day.

Bill Gates and company showed a prototype digital reader with side-by-side screens designed to emulate the experience of holding and paging through a National Geographic issue or the Wall Street Journal. At the time, I furiously took notes on a brick-thick Compaq laptop. Today, looking back and typing this on a Microsoft Surface, it’s now clear the digital reader was ahead of its time, even though it actually appeared after the glorious life and ultimate demise of Apple’s Newton tablet.

Technology evolves that way. Failures and reinventions. Big ideas that get fine-tuned until they fit just right and then catch fire. While Microsoft’s digital reader never made it to market, subsequent iterations of iPads and Android tablets took off.

That’s not just true of smartphones, tablets and 2-in-1s, either. It’s true, though in a manner admittedly less sexy and often invisible to people not directly involved, of industry standards as well. On that same day back at the turn of the century, Microsoft also unveiled the C# programming language and the .Net platform, as well as a concept blandly enough dubbed “web services.”

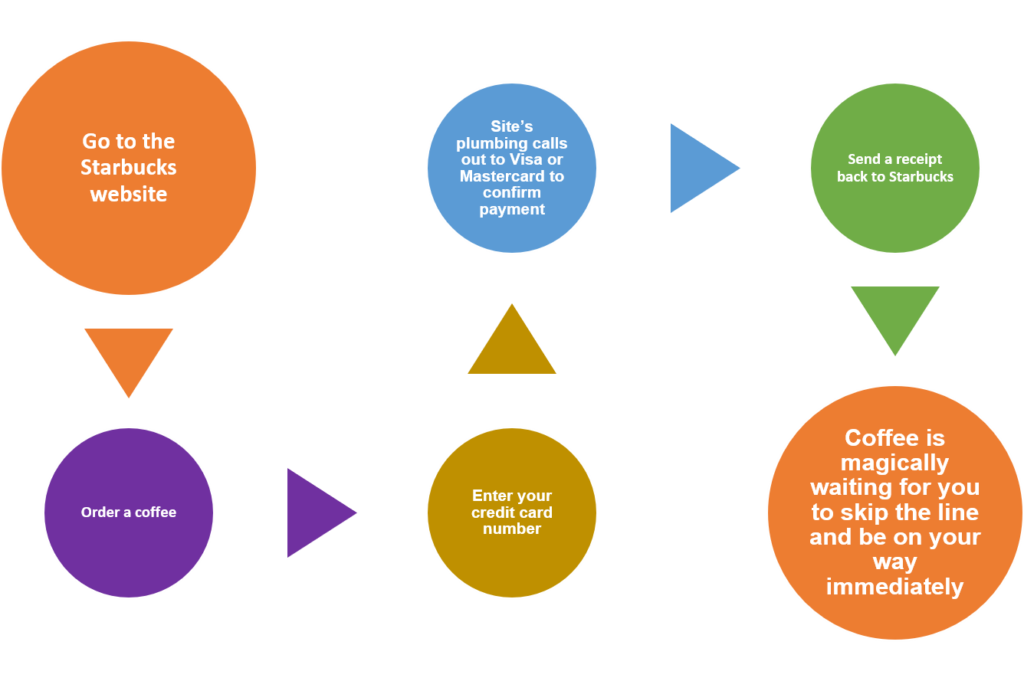

Executives demonstrated a web service that enabled a customer to pre-order Starbucks coffee so it could be ready and waiting when you arrived, thereby saving the time of waiting in line and paying on the spot:

Okay, the big problem for those of us on corporate-issued computers was that it took as long to fire up Windows 95 as it did to wait your turn on the Starbucks line. But it was a memorable, if crude, example of the sort of interoperability that foretold software being able to perform practical data exchange for everyday purposes that would change the world. And it was part of a broader effort that the biggest software giants were undertaking to enable real information sharing among their application server stacks so one website could talk to many others instead of point-to-point interfaces -- not altogether unlike the interoperability examples among EHRs today.

IBM, Oracle, Microsoft, Sun Microsystems, and a fistful of since-acquired vendors (BEA Systems and iPlanet, anyone?) came together in standards bodies to agree on specifications and compete on implementation. They would then take the specification back to their respective teams and essentially bend them as far as they could toward their own will. The process was painful and long but it ultimately paved the way for JSON and RESTful Web services used today.

All along the way, those standard makers even used the word interoperability; it’s not unique to healthcare by any means.

The future is FHIR

Despite the reality that it’s easy to go to HIMSS and think “we’ve been talking about interoperability for so long now it will never happen,” having witnessed and written about that era is part of the reason to be hopeful now more than ever before.

There are two main reasons for this: FHIR 4 and advancements made by Carequality and CommonWell.

Health Level Seven earlier this year released the normative Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) version 4 and foretold what FHIR 5 might look like. While FHIR 5 is on the horizon, FHIR 4 is the long-awaited version that will make apps developed with it compatible with future versions of the spec.

Carequality and CommonWell, for their part, turned on the ability for any member of either to share Continuity of Care Documents (CCD) with any other member – a milestone in its own right but by no means the end goal.

FHIR, along with the Carequality and CommonWell milestone, in fact, evoke the Starbucks site calling out to credit card companies to verify pre-payment for a coffee in that it’s not the endpoint of anything. For digital health, clinicians need more than a CCD data dump -- but it’s a noteworthy step in the right direction.

Today, even my neighborhood deli has a halfway decent app. No it’s not FHIR-based, but it does call out to a third-party service to validate payment. It’s not perfect interoperability -- I'd not say the user experience is delightful -- but it’s close enough to be useful.

At the very least, that app is faster than waiting in line. Interoperability doesn’t have to be perfect in a utopian sense, either -- which tells me that even though digital transformation is indeed a daunting task, we can do this.

About the author:

Tom Sullivan is the Editor-in-Chief & Director of Content Development at HIMSS Media. Sullivan writes the Innovation Pulse column for Healthcare IT News, and drives coverage of the HIT, people, policies and technologies underpinning the next generation of healthcare in America, from large health networks all the way down to solo practitioners and, of course, the most important aspect: patients.

Prior to HIMSS Media, Tom was News Editor of IDG's InfoWorld, directing a dozen reporters' coverage for the weekly print publication and daily website. He is a Neal finalist and multiple ASBPE award-winner whose work has appeared on CNN, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Healthcare IT News, Healthcare Finance News, and a range of technology publications, including Computerworld and PCWorld.