By Niall Brennan, MPP

President & CEO, Health Care Cost Institute

Introduction

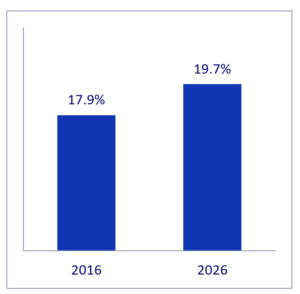

Health care spending is exceedingly difficult to control for our nation, the states, and private payers, but also for individual patients and providers. While there has been some moderation in spending in recent years in programs like Medicare, the health share of gross domestic product (GDP) is projected to continue to rise from 17.9 percent in 2016 to 19.7 percent in 2026 (see Figure 1).1

Figure 1. Projected GDP Health Share

Over the past decade, concerns about health care spending growth have prompted multiple initiatives, including price transparency efforts, to cure our health care spending woes.

Price transparency has become a widely accepted term in the healthcare lexicon, yet it lacks a standard definition, being liberally used to describe a varied and fragmented set of initiatives – from data sharing to consumer empowerment – all intended to rein in health care spending. But with no integrated approach, price transparency initiatives have been merely chiseling away at spending on individual components of a large, complex, and intractable health system with little measurable impact on overall spending. Despite these lackluster results, interest in price transparency remains strong, with a bipartisan group consisting of US Senators and the Department of Health and Human Services requesting public input on price transparency principles and proposals in recent months.2,3

A Transparent History

As new initiatives emerge, it’s important to recognize that consumer-focused price transparency initiatives are not new in health care. In 2007, the state of New Hampshire launched a price comparison shopping website for consumers4; in 2008, the health tech company Castlight was established to provide commercial solutions to help employers and their employees navigate the health care system; and in 2015, the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI), in partnership with United Health Group, Aetna, and Humana, created Guroo – a consumer-facing website that provides users with information on the relative prices of bundles of care for common health care services and procedures. As of 2018, more than half of all states have enacted laws either creating price transparency websites or requiring providers and insurers to reveal prices to patients, including the state of Florida, which is launching a facility-specific price transparency website based on the HCCI Guroo platform.5

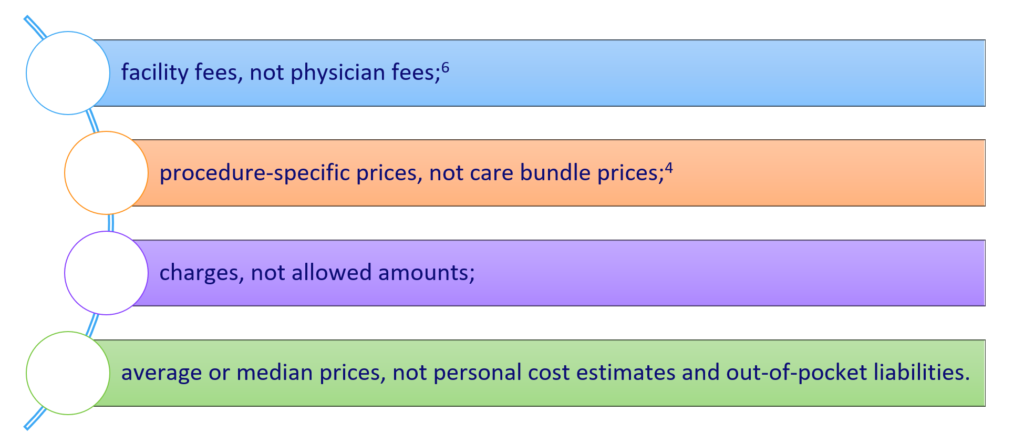

Despite the numerous consumer-focused price transparency initiatives to date, their actual and projected impacts on health spending remains limited at best. Consumer-facing price transparency tools, which provide patients with cost estimates and quality information for common shoppable services, have proven ineffective at reducing total health care spending. No two such tools are alike due to differing data sources and a lack of standards for defining and reporting health care prices. Though many tools provide meaningful components of the value of health care services, the vast majority include only partial price information: What value is there in tools that paint an incomplete, indigestible, and potentially misleading picture of what a consumer can expect to pay? We need to agree upon a standard definition of price across all services and develop better tools that empower consumers to make cost-effective decisions about their health.

What value is there in tools that paint an incomplete, indigestible, and potentially misleading picture of what a consumer can expect to pay? We need to agree upon a standard definition of price across all services and develop better tools that empower consumers to make cost-effective decisions about their health.

Shoppable Health Care

Even the most comprehensive tools that calculate personalized price estimates for outpatient services based on a consumer’s insurer and benefit design have been used by less than 13 percent of all individuals to whom they are offered.7 The few savvy consumers who do choose to price shop before seeking care typically do not save,7 and in some cases, spend more.7 Even if more consumers could be persuaded to shop for services for which price transparency searches have been shown to reduce spending – as much as 14 percent savings for medical imaging – the projected effect on total spending would be likely be inconsequential – less than a tenth of a percent reduction by one estimate.8

All this is not to say that consumer-focused price transparency is an exercise in futility, but it should serve as an appeal to temper expectations about the ability of price transparency to singlehandedly bend the cost curve. With approximately 35-43 percent of health care spending attributable to shoppable services,9 there exists an opportunity for consumer-focused price transparency to meaningfully bring down spending. Consumers are not necessarily opposed to price shopping, at least according to surveys in which they state that they want greater transparency and insights into the cost of their health care.10

Consumer-Driven Price Transparency

Perhaps the larger issue is that the failure of existing price transparency efforts speaks more to our collective failure to truly understand health care consumers and their needs. We frequently hear statements that when shopping for nearly anything but healthcare, we know the price before we make our purchase. But we don’t expect the average consumer to buy the individual components that comprise a car. And we certainly don’t tolerate a system where several weeks after buying a car the purchaser is informed that the maker of the airbags in the car was an out-of-network supplier and that the consumer now owes an additional $4,000.

Price transparency may not be a magic bullet, but it can be an important component in the multi-faceted process to reduce spending and create value in health care. Consumer-driven price transparency lacks standards, and the current tools are suboptimal. To expect it to succeed – where decades of interventions by government, payers, and providers have failed – is more than just disingenuous: it smacks of blaming the victim.

References

- NHE Fact Sheet. National Health Expenditure. 2018. Accessed May 27, 2018.

- Sen. Bill Cassidy. Cassidy Leads Bipartisan Group of Senators in Launching Health Care Price Transparency Initiative. Mar. 1, 2018.. Accessed Apr 20, 2018.

- Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 Medicare Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) and Long Term Acute Care Hospital (LTCH) Prospective Payment System Proposed Rule, and Request for Information. Apr 24, 2018.

- New Hampshire Insurance Department. NH Health Cost. 2018. . Accessed May 26, 2018.

- Kullgren JT, Duey KA, Werner RM. A census of state health care price transparency websites. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2437–2438.

- Oregon Hospital Guide. 2018. http://oregonhospitalguide.org/. Accessed May 26, 2018.

- Desai S, Hatfield LA, Hicks AL, et al. Association between availability of a price transparency tool and outpatient spending. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1874–1881.

- Desai S, Hatfield LA, Hicks AL, et al. Offering a price transparency tool did not Reduce overall spending among California public employees and retirees. Health Aff. 2017;36(8):1401-1407.

- Frost A, Newman A. Spending on Shoppable Services in Health Care. Health Care Cost Institute. Issue Brief Number 11. Web. March 2016.

- Mehotra A, Dean KM, Sinaiko AD, Sood N. Americans support price shopping for health care, but few actually seek out price information. Health Aff. 2017;36(8):1392-1400.

The author would like to acknowledge Dan Fulop, Research Assistant at HCCI for his help in producing this publication.

About the Author

Mr. Brennan was appointed President and CEO of HCCI in June 2017. In this role, he is responsible for overseeing HCCI’s advancements in price transparency and public reporting, increasing both the comprehensiveness and access to HCCI’s expansive data set, as well as working with state policy and decision makers to improve their healthcare systems. He is a nationally recognized expert in health care policy, the use of healthcare data to enable and accelerate health system change, and data transparency. He has published widely in leading academic journals, including the Journal of the American Medical Association, the New England Journal of Medicine and Health Affairs. Prior to joining HCCI, Mr. Brennan was Chief Data Officer at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). He has also worked at the Brookings Institution, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, the Congressional Budget Office, the Urban Institute, and Price WaterhouseCoopers.

Mr. Brennan received his MPP from Georgetown University and his BA from University College Dublin, Ireland.