By Mark Rosenberg, MD, MPP

President Emeritus, The Task Force for Global Health

Introduction

I went to graduate school in public policy believing that good policy flowed from good decisions made with good data. I thought that I might be able to contribute to better health and health care for many people if only I knew how to collect the data I needed and used it to make rational, evidence-based decisions. I was diligent in my studies and had superb teachers at a reputable school. But all the quantitative and qualitative analysis in the world didn’t prepare me for what I later encountered in the rough and tumble politics of gun violence. Here, not only are decisions being made in the absence of data, but steps have been taken to ensure that no data are generated, disseminated, or used. It took me quite a long time to learn from experience that, in fact, policy often develops in a data vacuum, where it is conceived and finalized to help achieve the goals of the policy proponents. And yet I remain optimistic.

I want to tell you why the situation with respect to gun violence prevention is neither hopeless nor depressing.

History of Gun Research

In the late 1970s and ‘80s, the National Rifle Association (NRA) developed a strategy that turned out to be brilliant for the NRA and absolutely disastrous for our nation. They saw that research on gun violence might pose a threat to the sale of guns and they told their membership that this research would result in members losing all their guns. It was an all-or-none decision: it was either research or guns, and they couldn’t have both. They had to choose. And they presented this same choice to legislators at every level of government.

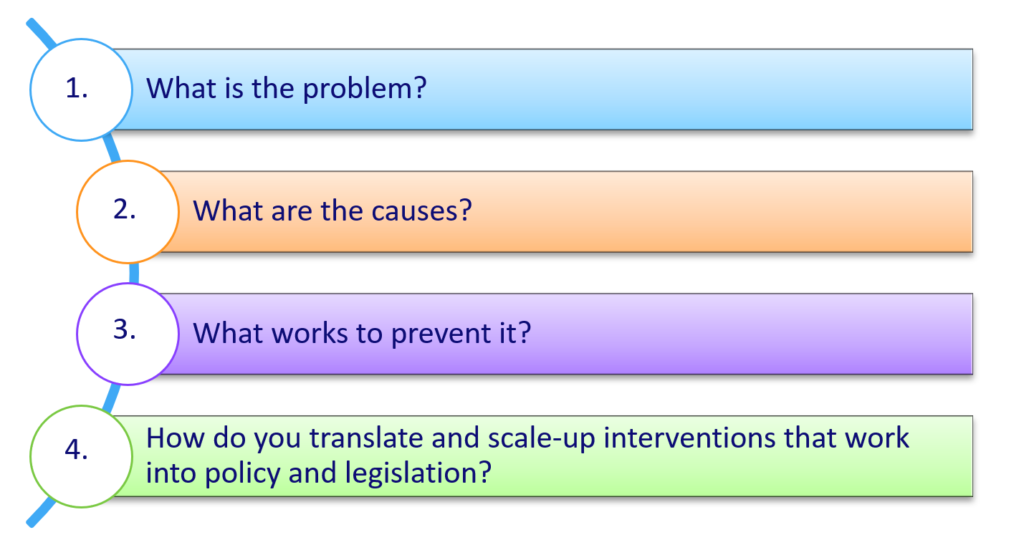

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had actually started to look at research on gun violence prevention because they had seen that research on another injury problem—motor vehicle crash deaths—had led to safer cars, safer roads, and safer drivers. These improvements had actually stopped an epidemic of highway traffic deaths and saved hundreds of thousands of lives. If research could find the answers to four basic questions about gun violence, it might save just as many lives. So starting in 1983, CDC scientists had set out to answer:

For years the NRA had been arguing that if you cared about keeping your home and family safe, you needed to have a gun in your house. And they had launched many separate attacks against CDC, calling its work on violence prevention “the cesspool of junk science.” But then came some CDC-sponsored research that really upped the ante. Papers published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine showed that having a gun in your home did not make you safer, but in fact greatly increased the risk that someone in your family would die from a gun homicide or suicide. At that point the NRA felt seriously threatened and decided the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control needed to be shut down. And Congressman Jay Dickey was chosen to lead the charge.

Meeting Jay Dickey

Jay Dickey and I met as enemies when the NRA’s attack came to a head at a congressional hearing on the CDC appropriations bill in April of 1996. Jay, as the congressional point man for the NRA, supported the strategy that the NRA leadership had developed in the 1970s to stop all public discussion of gun control and to make sure that research on this issue did not go forward. Their policy was one of zero tolerance. They told Jay that he had a choice: he could either allow research to go forward or he could keep his guns. But he could not have both. It was a black and white choice.

When Jay and I met we could not have been more different. He was a conservative Republican Congressman from very rural Arkansas, the duck-hunting capital of the world. He was a born-again Christian. And I was a liberal, curly-haired kid from the Northeast, born only once and born Jewish, and way over-educated, a term that was not meant as a compliment, suggesting instead that I knew little about how the real world worked. Jay led the charge at that hearing with the goal of abolishing CDC’s injury center in its entirety. If the center were doing research that the NRA didn’t like, then shut it down, never mind that injuries were the leading cause of death for all Americans between ages 1 and 45.

At that hearing, Jay ambushed me and David Satcher, the Director of the CDC, and challenged us with quotes taken out of context and quotes that I had never said. The CDC policy folks thought that the hearing had gone so badly and this subject became so inflammatory that they ordered me to never speak to “that Congressman.” They said if I ever spoke to him it would be like tossing a lighted match onto gasoline. But a few weeks later I received a request from Jay’s staffer to meet with him to review some of the data we had presented at the hearing. My CDC bosses said it would be okay for me to meet with the staffer but absolutely not with the Congressman, a serious mistake that limits the potential for true policy dialogue. Fortunately Jay felt differently. He said that whenever he met someone who held views quite different from his own, he wanted to talk to them to learn what they thought and why.

The Dickey Amendment

The Dickey Amendment was written as a compromise between those congressmen who wanted to abolish CDC’s injury center and those who wanted to fund even more gun violence prevention research. It stated that none of the funds appropriated to CDC could be used to advocate or promote gun control. To be sure, the Dickey Amendment did not prohibit gun violence research, per se. Technically it prohibited lobbying in support of specific gun control legislation, something that the CDC had not even been involved in and had no intention of doing. Instead, it was a shot across the bow, warning anyone doing or considering doing research in this field —or any administrator who might allow such research—that they had better think twice because any congressman opposed to such research could write a letter to a researcher or administrator claiming that the researcher was engaged in advocating or promoting gun control, whether they were or not. And it could take weeks or months of their time to craft an appropriate response to such a letter.

But Jay Dickey and I did meet. We talked, and we talked again. We started to know each other, to understand each other, trust each other, respect each other, even like each other, and learn from each other. But in 1999, when David Satcher left the CDC to become U.S. Surgeon General and Assistant Secretary for Health, a new director of the CDC was appointed and the director of the injury center, the person most closely associated with the gun violence prevention research program, was fired. Then the amount of funding going to gun violence research at CDC fell by more than 90%.

Keeping an Open Mind

I learned a tremendous amount from Jay and I think he learned something from me. Jay came to understand the power of science and the public health approach for solving difficult problems. I learned that it was important to state that the research had to find interventions that would both prevent gun violence and protect the rights of law-abiding gun owners. We both came to see that research can get us out of this deadly morass and called for the research to be restarted. We knew that there are win-win solutions, but we need the data and evidence to prove they are effective on both goals. Our friendship created a common ground on which learning could occur and on which a bipartisan coalition could be built. But we learned that facts and evidence don’t change people’s minds on the most important issues. Instead, Daniel Kahneman, who won the Nobel prize for helping to create behavioral economics, told us that evidence is used for defending or rationalizing pre-formed opinions. We form our most important opinions based on what we learn from people we trust and admire, not from reviewing the evidence for each side. This suggests that being open to the opposite opinion is a necessary and prior step that has to occur if two conflicting sides are to reach an agreement or form a coalition. People with opposite views must actually talk and listen to each other.

Jay and I were able to do that and we actually came to love each other. But this raises an important question: If both Jay and I were interested in understanding people with opinions that were so different from our own, and if we had so many core values in common, how did we get to the point where we were almost mortal enemies? Jay may have been the Christian, but I had St. Frances as my patron saint, with his statue on my desk and another in my garden. I loved what he said in the Prayer of St. Frances: “seek first to understand and then to be understood.”

I now believe that we came to meet as arch-enemies because we had come to believe that it was a choice between gun rights or gun control. Unknowingly, we had both bought into this idea. We both came to see that this was not true. And now we needed to convince a majority of legislators and the American people. Our most powerful argument would be supported by science, by generating the evidence that shows that there are interventions and policies that both reduce gun violence and protect gun rights. In addition, without this evidence, legislators would be shooting in the dark, not knowing what is safe and effective, and would be asked to approve measures that may prove deadly.

Future Research

Just like it worked for motor vehicle injuries, science can find those things that are both safe and effective. Science can show that it is not a case of safety vs. sales, not a case of research or guns. As with cars, science and sales can go hand in hand. Evidence will show the way forward, but it is human beings trusting each other and learning from each other that are needed to move us forward. The Dickey Amendment, while originally a barrier to research, now acts as a bridge to form the bi-partisan coalition we need to support the research. We need to keep the Dickey Amendment because now it provides cover for lawmakers who want to appropriate funds for research but don’t want to be accused of supporting gun control: the Dickey amendment assures that none of the funds provided for research will be used to promote or advocate gun control.

So, understanding the power of science and the evidence it can generate, and convinced of the ability of people to respect, listen, and learn from each other, I am optimistic that we will resolve this problem of gun violence -- more optimistic than ever before.

About the author:

Mark L. Rosenberg is President Emeritus of the Task Force for Global Health. Rosenberg served as Assistant Surgeon General at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) where he led its work in violence prevention and later became the founding director of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Rosenberg is board certified in both psychiatry and internal medicine with training in infectious diseases and public policy. He is on the faculty at Morehouse Medical School, Emory Medical School, the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University, chaired the advisory board for the Georgia State School of Public Health, and is on the visiting committee of the Harvard Chan School of Public Health. He also serves as vice-chair of the Georgia Global Health Alliance. He has authored more than 135 publications, and wrote two books: Patients: The Experience of Illness, and Howard Hiatt: How this Extraordinary Mentor Transformed Health with Science and Compassion. He also co-authored the books, Real Collaboration: What It Takes for Global Health to Succeed and Violence in America: A Public Health Approach. Rosenberg has received numerous awards including the Surgeon General’s Exemplary Service Medal and the Outstanding, Meritorious, and Distinguished Service Medals of the Public Health Service. Rosenberg is a director of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, a member of the National Academy of Medicine, and on the Executive Committee of the Transportation Research Board. He earned his undergraduate degree, as well as degrees in public policy and medicine, at Harvard University.

He has been married to Jill Rosenberg for 42 years and is the father of Julie and Ben and the grandfather of Maddie and Henry.

A marvelous presentation of an extraordinarily persuasive approach to one of the nation’s most important problems. We are lucky to have Dr Rosenberg and to have had Congressman Dickey.

Nice to see how evidence is used by two intelligent people with different opinions to find common ground. Hopefully other people and institutions will use this approach to other solve problems.