By Heidi Tibollo, MLS, BSN and Todd Feinman, MD

"Follow the evidence wherever it leads, and question everything.” ~Neil deGrasse Tyson

In the 1840’s, Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, chief resident of the Vienna General Hospital’s obstetric clinic, noticed a disturbing trend: women with physician assisted deliveries became infected and died at a much higher rate than women with midwife-assisted deliveries. Dr. Semmelweis deduced that because physicians performed autopsies and then immediately delivered babies, they were inadvertently transferring “cadaverous poisoning” to these women. Midwives did not perform autopsies. He proposed a connection between cadaveric cross-contamination and puerperal fever. He further theorized that thorough hand cleansing was key to stopping these deadly “poisonings”. To test this theory, all physicians at the facility were required to wash their hands in a chlorinated lime solution after performing an autopsy. As a result, the number of puerperal fever and deaths dropped significantly. This is a classic example of medicine’s early attempts at doing a clinical study to determine causation and treatment outcomes. Millions of studies have been performed since then. But it is the evolution of software and digital technologies that have ushered in the golden age of evidence-based healthcare.

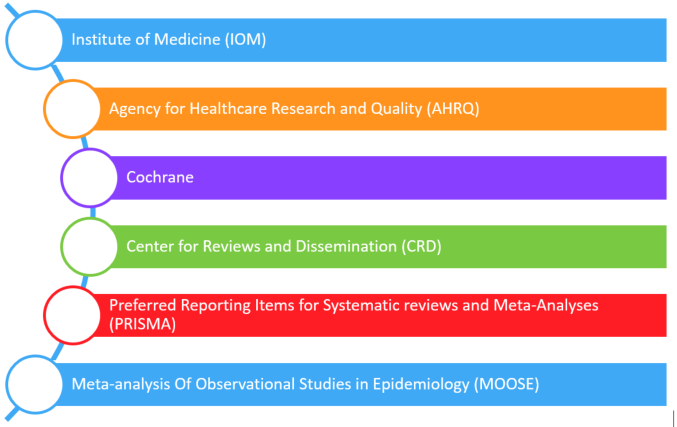

Evidence-based medicine should benefit all patients and their physicians. The need for accurate and timely evidence-based guidance is now an essential goal of our healthcare system that demands high quality and cost-effectiveness. But are we achieving this goal? Currently, numerous resources are available that enable policy makers and authors to aggregate and critically analyze published studies that will be included in a systematic review and/or meta-analysis. These resources include, but are not limited to:1-8

While much effort has been put forth for process improvement of the creation of systematic review and meta-analyses, a review of the current literature examining the quality of some of the current systematic reviews and meta-analyses shows there still is room for improvement.

Methods matter when it comes to producing valid, trustworthy, and useful information that will lead to better healthcare decisions and, ultimately, improved patient outcomes. PCORI

Reliability, Relevance, and Transparency

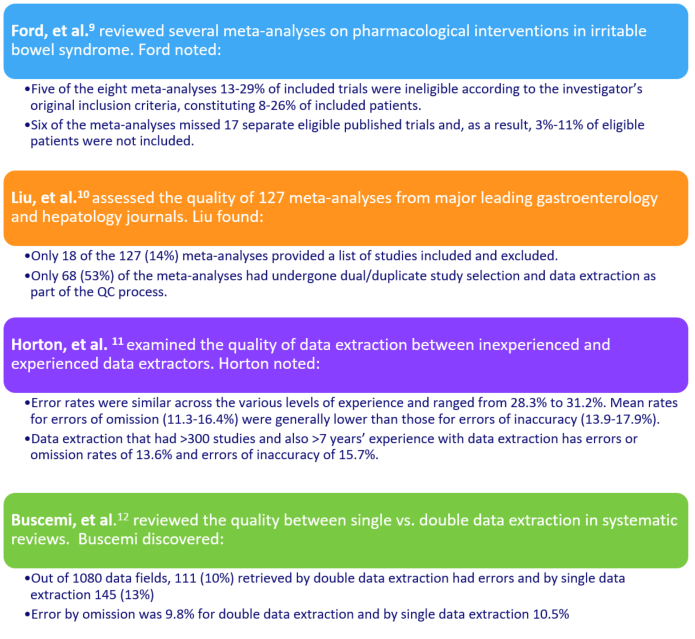

What is value of the final analysis if the data synthesis, extraction, and methodologies result in issues with relevance, reliability, and transparency? While numerous organizations provide guidance and standards for performing search, data extraction and analysis, compliance with these standards and processes are not evident in many published systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Some examples from published studies on the quality of published meta-analyses:

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: Forward looking

Like Dr. Semmelweis, policy makers and guideline authors need to adopt new processes that are proven to improve quality of care provided to patients. This requires the regular surveillance for, and resolution of, errors and issues that can impact the reliability and relevance of the published systematic reviews and meta-analyses on which they are relying to create conclusions and recommendations on behalf of real patients and doctors.

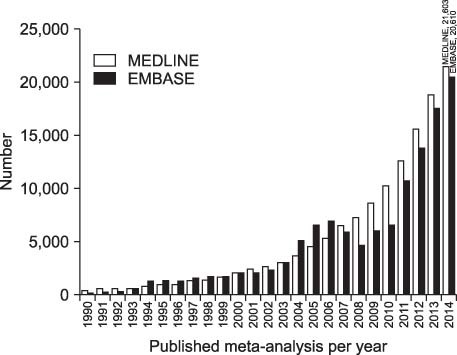

Currently, PubMed is nearing 27 million references (as of this writing the total in PubMed is 26,992,110). A recent five-day-span search of PubMed for all references in the database showed a growth of 12,313 references added to the PubMed database. Given it is nearly impossible now to review and analyze this increasing volume of clinical trials, the guideline industry must adopt or demand processes (i.e., double extraction) and/or emerging technologies (i.e., machine learning, digital evidence, natural language processing, etc.) that enable maximum reliability, relevance and transparency of published systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Kim, et al. 12

Kim, et al. 12

Additionally, with the increasing demand for “living” systematic reviews13 and guidelines14, 15 the evidence-based medicine industry needs even greater efficiencies for “updating” systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and the guidelines that depend on the new clinical studies that have been published.

Those who embrace evolving technologies and processes that are proven to improve search, extraction, and analysis will lead the way to fulfilling the promises of evidence-based medicine. More than 150 years ago, doctors eventually embraced hand washing after reviewing the evidence. In the near future, the leading authors of systematic reviews, meta-analyses and guidelines will want to significantly improve guidelines after reviewing the evidence on existing guideline issues. And once again, our healthcare system will embrace another behavior that will improve patient outcomes.

I believe in evidence. I believe in observation, measurement, and reasoning, confirmed by independent observers. I'll believe anything, no matter how wild and ridiculous, if there is evidence for it. The wilder and more ridiculous something is, however, the firmer and more solid the evidence will have to be. - Isaac Asimov

References:

- Morton S, et al. (Eds). Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews. National Academies Press, 2011.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008.

- Higgins JP and Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Vol. 4. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 1998-.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews. 2015;4(1)1.

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012.

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647.

- Ford AC, Guyatt GH, Talley NJ, et al. Errors in the conduct of systematic reviews of pharmacological interventions for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(2):280-288.

- Liu P, Qiu Y, Qian Y, et al. Quality of meta‐analyses in major leading gastroenterology and hepatology journals: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(1):39-44.

- Horton J, Vandermeer B, Hartling L, et al. Systematic review data extraction: cross-sectional study showed that experience did not increase accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(3):289-298.

- Buscemi N, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, et al. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(7):697-703.

- Kim HJ and Ahn HS. Critical Appraisal of Systematic Review/Meta-analysis. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res, 2015;15(2):73-79.

- Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med, 2014;11(2):e1001603.

- Lewis SZ, Diekemper R, Ornelas J, et al. Methodologies for the development of CHEST guidelines and expert panel reports. CHEST. 2014;146(1):182-192.

About the authors:

Todd Feinman, MD

Dr. Feinman is the Chief Medical Officer and co-founder of Doctor Evidence. A graduate of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California (UCLA Medical School), Los Angeles, Dr. Feinman completed his internship at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, and his residency in Internal Medicine at Huntington Memorial Hospital in Pasadena, California. As a board-certified internist, Dr. Feinman helped develop one of the the first Hospitalist programs in Southern California and later helped launch hospitalist programs at other medical centers in LA county. As a Hospitalist and Medical Director for a large, independent physician association, Dr. Feinman realized that there were no user-friendly technologies that would enable him, or others, to use the data found in clinical studies to determine the most effective test or treatment for specific patient populations. As CMO of Doctor Evidence, Dr. Feinman has helped architect evidence databases for patients/physicians all over the world, Kaiser, medical societies and many of the top pharma/device companies.

At Doctor Evidence, Dr. Feinman aims to continue creating revolutionary evidence technologies that will lead to real healthcare reform in America. This includes the current foundational partnership between USC Center of Body Computing and Doctor Evidence to create a “virtual doctor” technology that will revolutionize how patients and their physicians make informed decisions in the future.

Heidi Tibollo, MLS, BSN

Medical Librarian

Heidi Tibollo has been employed as a medical librarian at Doctor Evidence LLC for three years. Prior to Doctor Evidence she has worked as a librarian for a privately-owned organization and a public library system. She has collaborated on projects for both the UCLA Health System Institute for Innovation in Health and The Network for Excellence in Health Innovation. Prior to working as a librarian Heidi had a career in nursing. Her nursing experience includes: pediatrics, ophthalmology, intensive care and HEDIS patient chart review. During her free time, Heidi volunteers as a citizen scientist for Mark2Cure and is an active member of the Medical Library Association Systematic Reviews Special Interest Group.