By Susan Dentzer

President and CEO, Network for Excellence in Health Innovation (NEHI)

Former senior policy adviser for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Former editor-in-chief, Health Affairs

Unraveling the ACA

When it comes to health policy at the highest levels of the U.S. government, evidence has “left the building.” How else to describe what has occurred since January 2017 in efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA)? Although wholesale attempts to repeal the law failed, death by a thousand cuts to the law continues; witness the effective repeal of the law’s “shared responsibility” provision, or individual mandate, in the tax law enacted late last year. Not surprisingly, there are now early signs that the rate of health insurance coverage – which had been climbing since the ACA’s enactment in 2010 – is now on the decline.1

What has enabled the ACA’s partial undoing is the triumph of ideology and raw politics over evidence. Many Republicans not only despise former President Obama, but they also detest particular provisions of the ACA – including the expansion of Medicaid to populations viewed as “able-bodied” and thus unworthy of government assistance.2 So passionate is the opposition that there has been an almost complete disregard of “evidence,” at least as sober-minded thinkers might understand the term. This neglect has been accompanied by the breakdown of “regular order” – the rules and customs of Congress that once created at least a semblance of orderly and deliberative policymaking.

Evidence (or not) in Policy

To write this is not to pretend that there was once a Golden Age when only evidence worthy of publication in peer-reviewed journals carried the policymaking day. As David Blumenthal and James A. Morone observe in their compelling history, The Heart of Power, President Lyndon Johnson in 1964 so desperately wanted to enact Medicare that he didn’t care what was in the bill to create it, insisting “I trust you on the details.”3 In fairness to Johnson, the fight over creating government-financed hospital insurance for the elderly had already raged for more than a decade, amid ample evidence that senior citizens were suffering without it.

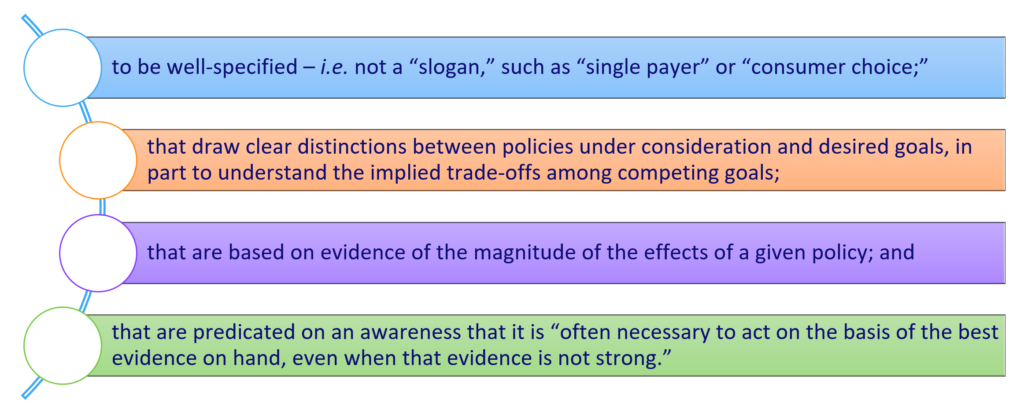

But to illustrate how bad things have become since then, consider the excellent framework for “evidence-based health policy” set forth by Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra,4 and the gap between their framework and what has occurred with the ACA. This four-part approach calls for policies:

Of the four elements of this framework, how many were followed during the 2017 debate over repealing and replacing aspects of the ACA? Arguably only the last one – the awareness of the need to act before all the evidence was in. Even then, the rationale for acting quickly was fatuous. With Donald Trump’s unexpected victory in November 2016, the Republican-dominated Congress simply felt that it had to act fast to put real meat on the bones of the longstanding slogan “repeal and replace.”

A full analysis of what resulted is beyond the scope of this commentary, but one aspect of it – the drive to repeal the so-called individual mandate – illustrates the point. The provision was at the center of the Supreme Court’s decision in 2012 upholding the ACA, and was targeted for elimination in multiple “repeal and replace” bills. Ultimately, the de facto repeal was hastily incorporated into the final version of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act, when the penalty for non-compliance with the mandate was reduced to zero.5

Individual Mandate

Exactly what was the “evidence” either for or against the individual mandate? Most comes from Massachusetts, which adopted a similar provision in its 2006 health reform law. Subsequent research suggested that the Massachusetts mandate fulfilled its rationale of bringing more healthy people into the state’s reformed health insurance market, thus preventing adverse selection and higher premiums.6 As to the effects of repealing the ACA’s individual mandate, one of the few rigorous analyses was performed by the RAND Corp. researchers with the aid of RAND’s COMPARE microsimulation model, which predicts the effects of health policy changes at national and state levels. The RAND study found that eliminating the individual mandate would cause relatively small increases in premiums, but large declines in the number of people insured. It also predicted that repealing the mandate would cost the federal government more than retaining it, both through lower penalties and forgone tax revenue, as well as the higher costs of subsidizing coverage for a more expensive population.7

Later analyses by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) echoed the finding that repealing the mandate would cause a huge jump in the number of uninsured, to 13 million more by 2027, and a ten percent increase in health insurance premiums.8 Acknowledging uncertainty around the estimates, the CBO and JCT said that the result would actually be to reduce the federal budget deficit, since with fewer insured individuals, expenditures on the ACA’s insurance subsidies would fall.

Did members of Congress who eventually voted for an effective repeal of the individual mandate want to increase the number of uninsured and drive up premiums for the sick? Most likely not; they just rejected the evidence. Yet as the tax bill rocketed through Congress, no formal hearings were held on the final version that included the effective mandate repeal. No analysis was sought of the increases in morbidity and mortality that almost certainly would follow. After all, still more evidence from Massachusetts shows that increased health insurance coverage produced significant reductions in all-cause and healthcare-amenable mortality, compared to demographically similar areas nationally.9

Future of Healthcare Policy

Now that evidence is ignored or dismissed as irrelevant, policy trade-offs are not even framed, and facts disappear amid a rain of anecdotes or untruths, will things ever change? Perhaps, but I wouldn’t bet on it. In a November 2017 Gallup poll,10 roughly the same proportion of respondents said they favored “a government run health care system” (47 percent) to “a system based mostly on private health insurance” (48 percent). Does either phrase constitute anything beyond sloganeering about national health policy? In fact, “left the building” may be the most positive spin to put on the role of evidence in congressional health policymaking. Maybe, like Elvis, evidence is just dead.

References:

- Auter, Z. U.S. Uninsured rate rises to 12.3% in third quarter. Gallup. October 20, 2017. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- See, for example, comments by Alabama Republican Rep. Gary Palmer as reported here: Tribune Staff. Rep. Gary Palmer votes against Obamacare replacement in committee. The Trussville Tribune. March 16, 2017. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- Blumenthal D, Morone JA. The Heart of Power: Health and Politics in the Oval Office. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2009:179.

- Baicker K, Chandra A. Evidence-Based Health Policy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2413-2415. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1709816

- See, for example: Conference agreement for H.R. 1 – initial observations. KPMG. December 20, 2017. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. The importance of the individual mandate: evidence from Massachusetts. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:293-295. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1013067

- Eibner C, Saltzman E. How does the ACA individual mandate affect enrollment and premiums in the individual insurance market? RAND Corporation. 2015. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- Congressional Budget Office. Repealing the individual health insurance mandate: an updated estimate. November 2017. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- Sommers BD, Long SK, Baicker K. Changes in mortality after Massachusetts health care reform: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:585-593

- Newport F. In U.S., Support for Government-Run Health System Edges Up. Gallup. December 1, 2017. Accessed April 9, 2018.

About the Author:

Susan Dentzer is the President and Chief Executive Officer of the NEHI, the Network for Excellence in Health Innovation, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization composed of more than 100 stakeholder organizations from across all key sectors of health and health care. NEHI’s mission is to advance innovations that improve health, enhance the quality of healthcare, and achieve greater value for the money spent. With offices in Washington, DC, and Boston, Massachusetts, NEHI conducts independent, objective research and thought leadership to accelerate these innovations and bring about changes within health care and public policy.

One of the nation's most respected health and health policy thought leaders and journalists, and a frequent speaker and commentator on television and radio, including NPR, Dentzer previously served as senior policy adviser to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Prior to that, she was editor-in-chief of the journal Health Affairs, and from 1998 to 2008, she served as the on-air Health Correspondent for the PBS NewsHour.

Dentzer is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine and the Council on Foreign Relations. She is a member of the Board of Directors of the International Rescue Committee, a leading humanitarian organization; a member of the board of directors of Research!America, which works to advance research to improve health; and a member of the board of directors of the Public Health Institute. She is a fellow of the National Academy of Social Insurance and The Hastings Center, an institution dedicated to bioethics and the public interest. She previously served as a public member of the American Board of Medical Specialties. She serves on multiple advisory boards, including those of the Duke-Margolis Center; the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California-San Francisco; and the March of Dimes public policy advisory group.

A graduate of Dartmouth, Dentzer formerly chaired the Dartmouth Board of Trustees, and is a member of the Board of Advisors of Dartmouth Medical School. She and her husband, Charles Alston, have three grown children.

The opinions expressed in GROWTH Commentaries are those of the authors.