By Abdul R. Abdullah, M.D.

Science and Medicine Advisor, Clinical Research and Policy

American Heart Association | American College of Cardiology

The American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) have made guideline modernization a priority, because staying technologically current and providing accessible, high-quality guidance to those facing modern challenges in health care is important for these organizations. To that end, the AHA and ACC envision modernization of their guidelines by continuously applying methodological and technological improvements in both document development and management of authorship. These initiatives, in turn, facilitate guideline dissemination and utilization at the point of care.

I. Background

The AHA and ACC are leaders in clinical practice guideline development among medical specialty organizations. Their documents are widely considered high quality and authoritative. These organizations thus perceive themselves as owing a duty to cardiovascular health professionals and patients to deliver updated, high-quality, evidence-based guidance, and to do so rapidly, efficiently, consistently, and accessibly. The ultimate goal of the AHA and ACC is to move toward a “living guideline” concept, where evidence and recommendations are updated dynamically as needed.

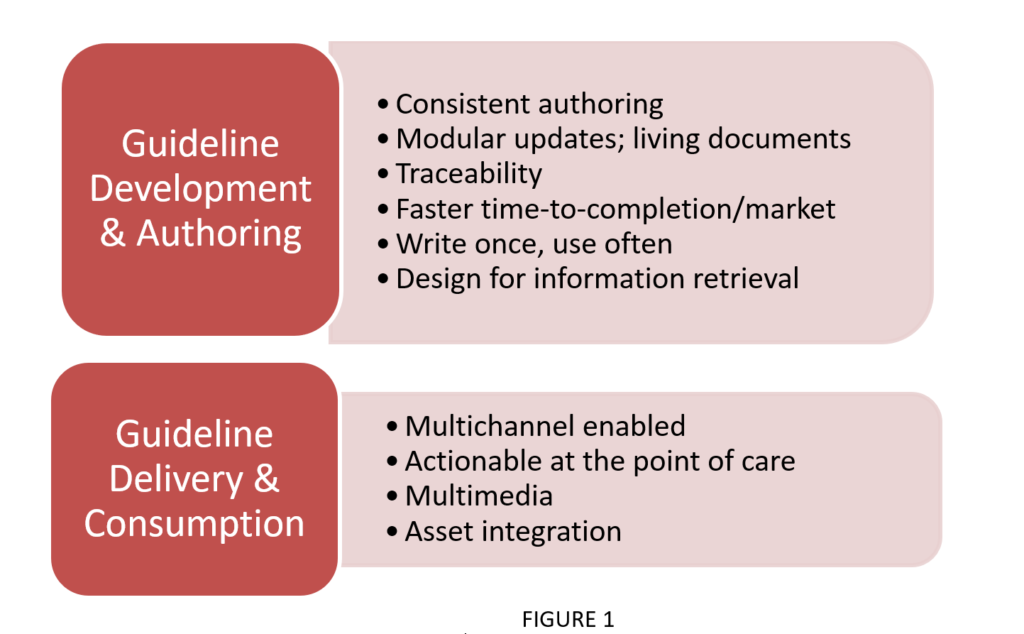

Modernization is relevant at both the development and authorship stages, as well as the delivery and consumption stages. The key principles (see Figure 1) operating under these two umbrellas are:

II. Modernization Efforts in Methodology

The AHA and ACC recognize that modernization efforts must extend beyond content-related systems. Methodology must be continually updated because the framework within which guidelines are presented is crucial to effective delivery. In particular, the joint organization focuses on three areas.

A.The Look and Feel of the Guidelines:

The AHA and ACC have identified and applied specific format-related principles that propose to make guidelines more user-friendly. For example, a new standardized guideline format: (1) aims to reduce the number of pages for each guideline, (2) requires executive summaries comprising of just the recommendations, pertinent tables, figures, and algorithms, (3) implements a “Modular Knowledge Chunk” format to facilitate rapid updates of specific groups of recommendations, and (4) encourages generous use of flow diagrams.

B. Standards for Developing Guidelines:

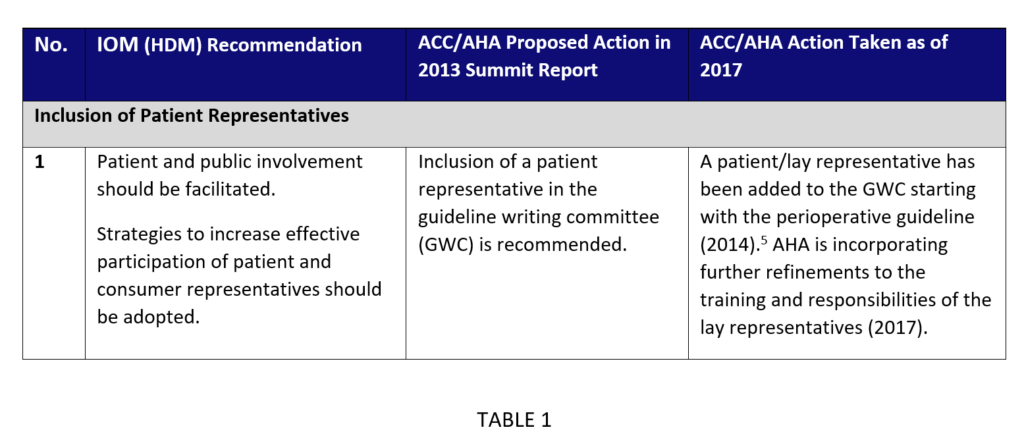

The ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines (TFPG) continually reviews, updates, and amends its guideline development methodology on the basis of de novo research by the in-house methodologists, its methodology summit,1 and the published standards from organizations, including the Institute of Medicine (IOM), now known as the Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies).2,3 In particular, TFPG recognizes the need to rigorously reevaluate its approaches according to consensus-based standards from the IOM and the immense experience brought to producing these authoritative documents in the field.

In this context, the AHA and ACC begin with ensuring compliance with IOM standards for developing clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). In 2011-2012, the AHA and ACC convened a methodology summit resulting in the publication of a summit report in 2013. The summit confirmed the AHA and ACC’s compliance with IOM standards, and highlighted the need for innovative approaches to maintaining compliance.1 These CPG standards are summarized on the National Academies website.

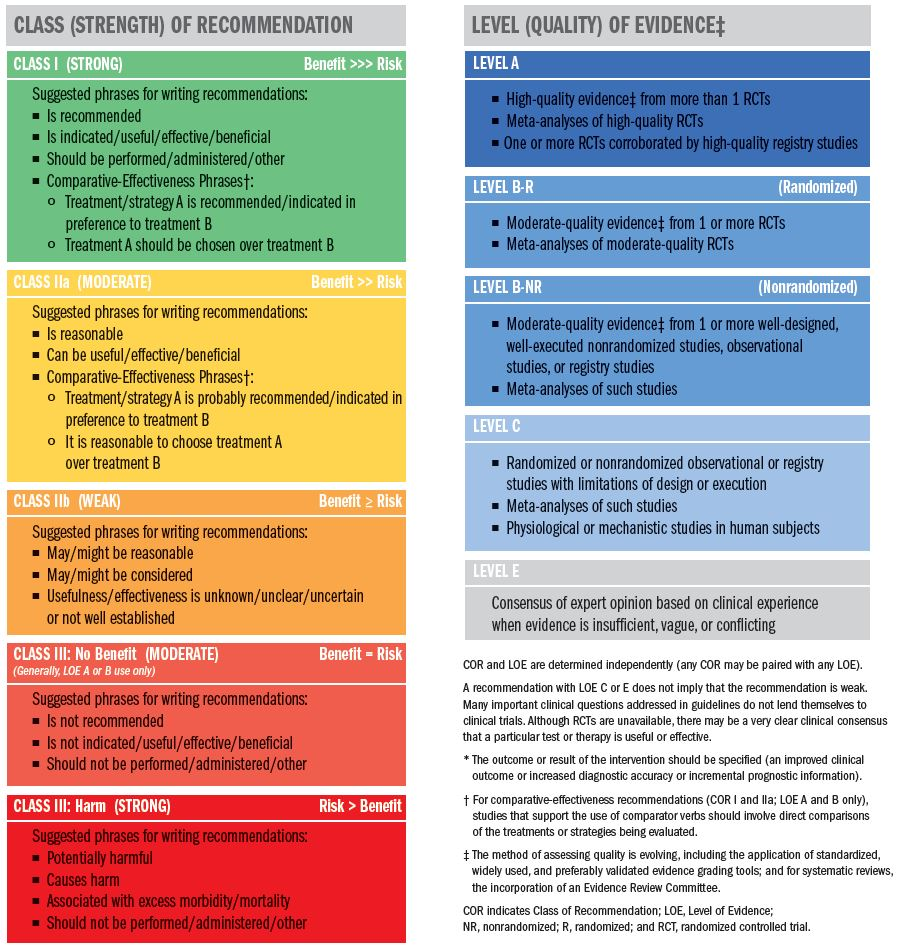

Building on the IOM standards, the AHA and ACC provide granular frameworks on class of recommendation (COR) and level of evidence (LOE) pertinent to the CPGs (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

However, for certain areas, the AHA and ACC have further enhanced methodology to account for findings and experience gathered through methodology summits and internal discussions. In these areas, the AHA and ACC’s goal is to maintain concordance with the IOM (HMD) recommendations and build on them, by placing a recommendation aside its proposed actions and current actions taken. These areas include managing conflicts of interests (relationships with industry and other entities), inclusion of patient representatives, comprehensive evidence reviews, systematic reviews, and peer review processes (see Table 1 for an example).

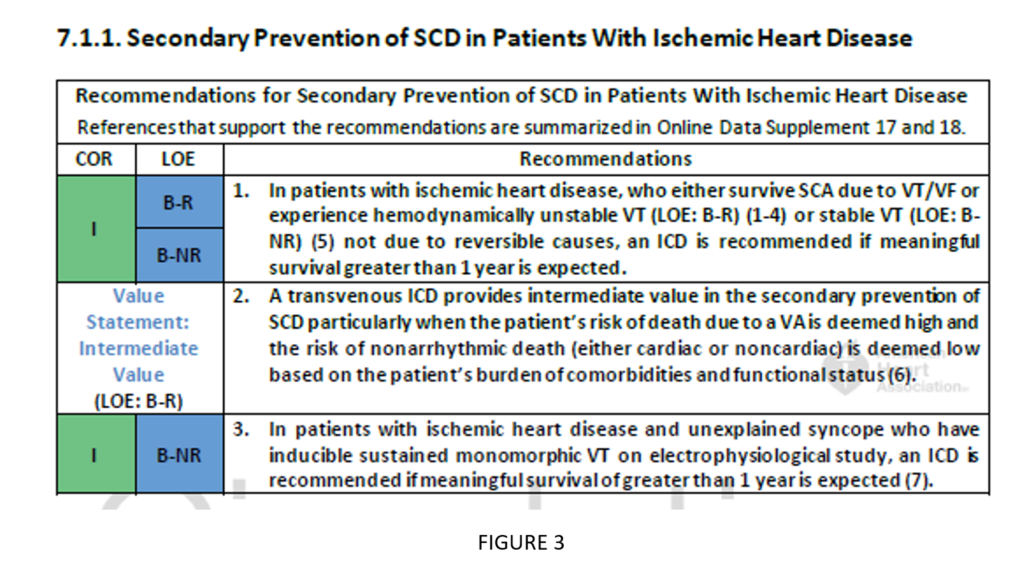

C. Cost/Value Analyses

Evaluations assessing the costs of implementing guidelines compared with the value added by implementation are encouraged whenever feasible. The ACC and AHA have developed methodology guidance to help with such analyses.4 These assessments allow a more tangible recognition of the use of the guidelines (see Figure 3).

III. Modernization Efforts in Systems

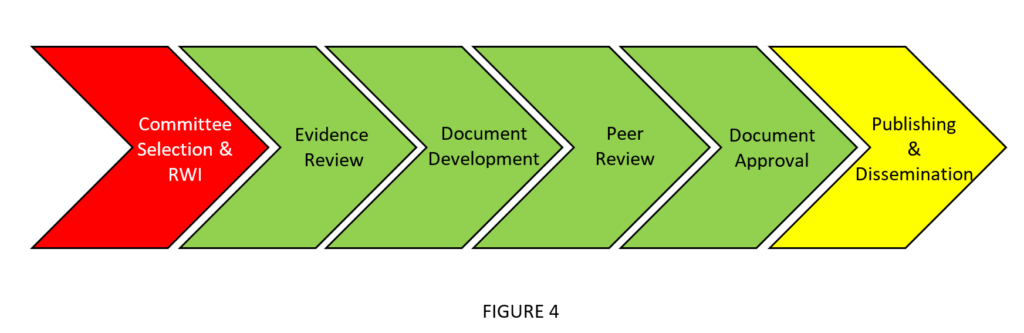

The AHA and ACC have adopted content-related measures to assist with systematic and peer review processes. In the joint organization’s flow for guideline development (see Figure 4), these measures are particularly helpful at the evidence review and peer review stages.

The AHA and ACC undertook a comprehensive request for proposal solicitation and analysis in 2013-2014. They found that Doctor Evidence (DRE) and Indico Systems were best suited to its selected systematic reviews (meta-analyses) and content management system, respectively, and have engaged each vendor to assist in guideline development. Additionally, the AHA and ACC are currently evaluating whether there are systems’ modernization steps that can be taken to improve further objective metrics.

A. Systematic Reviews Conducted Independently by the AHA and ACC Evidence Review Committees or within DRE Systems

The AHA and ACC conduct systematic reviews either independently with the volunteer evidence review committees or DRE. When DRE is used, they help scope the systematic review questions [Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Timing, Setting (PICOTS) questions] initially developed by the AHA and ACC writing and evidence review committees. DRE also advises on library search strategy, data extraction, quality control of extracted data with methodologic support as needed, and provides an interface for meta-analytic tools.

B. Indico Systems

Indico provides a content management system for peer review, documentation for tracking content, and resources for balloting recommendations.

C. Additional Metrics for Systems Improvements

The AHA and ACC continue to explore possibilities for further enhancing their use of systems to keep current with the changing technological environment. Specifically, the AHA and ACC are interested in tools that will allow for:

- Faster time-to-completion/market

- Reduced burden on volunteers and staff

- Increased capacity

- The ability to tackle additional PICOTS questions

- Systematic review approaches

- More rapid scenario analysis

- Evidence quality control

One initiative already under development is the use of guideline apps for use with mobile and portable technology. These apps are intended for use by both the organization and implementation at the point of care.

IV. Exemplary Modernized Guidelines and Systematic Reviews

To date, the following AHA/ACC guidelines have directly benefited from the modernization efforts described in this commentary. The AHA and ACC strive to continue its implementation of these initiatives, with the goal of keeping current with the needs of the industry (see List 1).

- 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery5

- SR—Perioperative beta blockade in noncardiac surgery SR 20146

- 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia7

- SR—Risk stratification for arrhythmic events in patients with asymptomatic pre-excitation 20158

- 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease9

- 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope10

- SR—Pacing as a treatment for reflex-mediated (vasovagal, situational, or carotid sinus hypersensitivity) syncope SR 201711

- 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death12

- SR—Ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death SR 201713

- SR—Dual antiplatelet (DAPT) guideline SR 201614

- 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults15

- SR—High blood pressure guideline SR 201716

List 1

References

- Jacobs AK, Kushner FG, Ettinger SM, et al. ACCF/AHA clinical practice guideline methodology summit report: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:268-310. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31827e8e5f.

- Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, et al. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:2329-2345. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000042.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:e278-e333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000106.

- Wijeysundera DN, Duncan D, Nkonde-Price C, et al. Perioperative beta blockade in noncardiac surgery: a systematic review for the 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2246-2264. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000104.

- Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society [published correction appears in Circulation. 2016;134:e234-235]. Circulation. 2016;133:e506-e574. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000311.

- Al-Khatib SM, Arshad A, Balk EM, et al. Risk stratification for arrhythmic events in patients with asymptomatic pre-excitation: a systematic review for the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2016;133:e575-e586. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000309.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2017;135:e791-e792]. Circulation. 2017;135:e726-e779. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000471.

- Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017;136:e60-e122. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000499.

- Varosy PD, Chen LY, Miller AL, et al. Pacing as a treatment for reflex-mediated (vasovagal, situational, or carotid sinus hypersensitivity) syncope: a systematic review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2017;136:e123-e135. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000500.

- Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society [published ahead of print October 30, 2017]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000548.

- Kusumoto FM, Bailey KR, Chaouki AS, et al. Systematic review for the 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society [published ahead of print October 30, 2017]. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000550.

- Bittl JA, Baber U, Bradley SM, et al. Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy: a systematic review for the 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2016;134:e195-e197]. Circulation. 2016;134:e156-e178. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000405.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published ahead of print November 13, 2017]. Hypertension. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065.

- Reboussin DM, Allen NB, Griswold ME, et al. Systematic review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published ahead of print November 13, 2017]. Hypertension. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000067.

About the author:

Abdul R. Abdullah is a member of the senior joint AHA/ACC Taskforce staff. Dr. Abdullah advises the organizations on guideline development methodologies, science, and procedures with the goal of developing trustworthy clinical practice recommendations for disease prevention, diagnosis, and management in the cardiovascular field. These guidelines, issued by the joint Taskforce, meet the highest standards of systematic scientific rigor and are intended to become policy amongst healthcare practitioners.

Dr. Abdullah is a physician and received formal clinical research training in the design and conduct of clinical trials/studies at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston in affiliation with the Harvard School of Public Health. He received his medical degree from Allama Iqbal Medical University in Lahore, Pakistan.

Prior to joining AHA and ACC, Dr. Abdullah worked as a clinical lead on behalf of a number of pharmaceutical companies for various drugs in different phases of development in the neuropsychiatric arena. He collaborated on several clinical research projects at MGH prior to joining AHA and ACC. Dr. Abdullah has also served as a co-principal investigator on several clinical trials/studies at the Stroke Service in the Department of Neurology at MGH.