By David Sampson, MBA

Vice President and Publisher, Journals, American Society of Clinical Oncology

Introduction

I began my career in medical publishing the year that U2’s The Joshua Tree won the Grammy for best album of the year. Back then journal publishers delivered print issues to individuals and libraries and maybe sold advertising and article reprints. We relied on “dead tree” direct mail marketing designed with phototypesetting machines producing galleys of type pasted onto layout boards. Article manuscripts were submitted, reviewed, and edited by mail or fax. And the emphasis in marketing was on the attributes of the journal instead of the value of individual articles.

One day in the early 1990s, my boss at the time asked me how I thought the internet would change our business. I had no idea what she was talking about during that meeting. But I remember signing up soon after that conversation for a dialup service called Prodigy to learn about the internet. Few of us who were new to scientific publishing had any idea what winds of change were beginning to blow.

Some history

In the mid-1990s, I was involved with the launch of T.E.A.L.: The Electronic Anesthesiology Library on CD-ROM, a five-year archive of four leading anesthesiology journals all on one disc (!), which you can still purchase today (used) on Amazon. In 1994, Stanford University launched HighWire Press, the first online journals hosting provider for publishers, a company that serves publishers to this day. For some perspective, Amazon and Netscape also launched that same year.

Fast forward to today and U2 is still making music and publishers are still printing paper issues of journals, albeit many fewer. Manuscript submission, peer-review, and editing have moved online. New technologies – from article-level alternative metrics to artificial intelligence (AI) – are revolutionizing content engagement, discovery, access, and publishing processes. Social media has added a powerful but sometimes risky option to the marketing toolkit. And the growth in content access via smartphones continues to outpace desktop computers and tablets.

Culture shift

While technology has enabled many publishing advancements, culture and ethos are fueling the winds of change. Using an electric fan as a metaphor, a collective of open science stakeholders, from patient advocates to research funders, are dialing up the speed on publishers to embrace open access and open data publishing. In their opinion, traditional scientific publishing is slow, susceptible to bias, and its outputs too often locked behind publisher paywalls in the form of growing subscription fees that libraries can no longer sustain and individuals cannot afford. Open science advocates argue that research products – lab notes, protocols, data, statistical analysis plans, analytic code, and papers (interim and final versions) – which taxpayers have largely paid for, should be open and freely accessible with liberal re-use rights. Research needs to be faster and more collaborative and the current publishing system simply impedes the rate of scientific progress.

In response, government agencies, private funders, and corporations are increasingly mandating open science policies such as the submission of data sharing plans on grant applications. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation now requires publication in an open access journal with the underlying data accessible and open immediately.1 The Gates Foundation and Wellcome Trust both launched their own open access publishing platforms (Gates Open Research and Wellcome Open Research) last year with F1000Research, a publisher that advocates for and supports an open peer review model. In January this year, the biotech company Shire Plc announced a new policy requiring all Shire-supported research to be published open access.

The rapid growth in raw manuscript uploads to preprint sites such as bioRxiv, which is partially funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, signals a publishing paradigm shift in life sciences research. John Inglis, a co-founder of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s bioRxiv, shared recently that more than 20,000 manuscripts have been uploaded representing 112,000 authors from 7,100 institutions and 104 countries with the U.S. and the U.K. leading the way, and the top five disciplines being neuroscience, bioinformatics, evolutionary biology, genomics, and genetics.2 medRxiv, a preprint site for medicine and the health sciences out of Yale University, is expected to launch in the near future. In March 2017, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a notice encouraging investigators to use preprints “to speed the dissemination and enhance the rigor of their work” and allow investigators to “cite their interim research products and claim them as products of NIH funding.”3

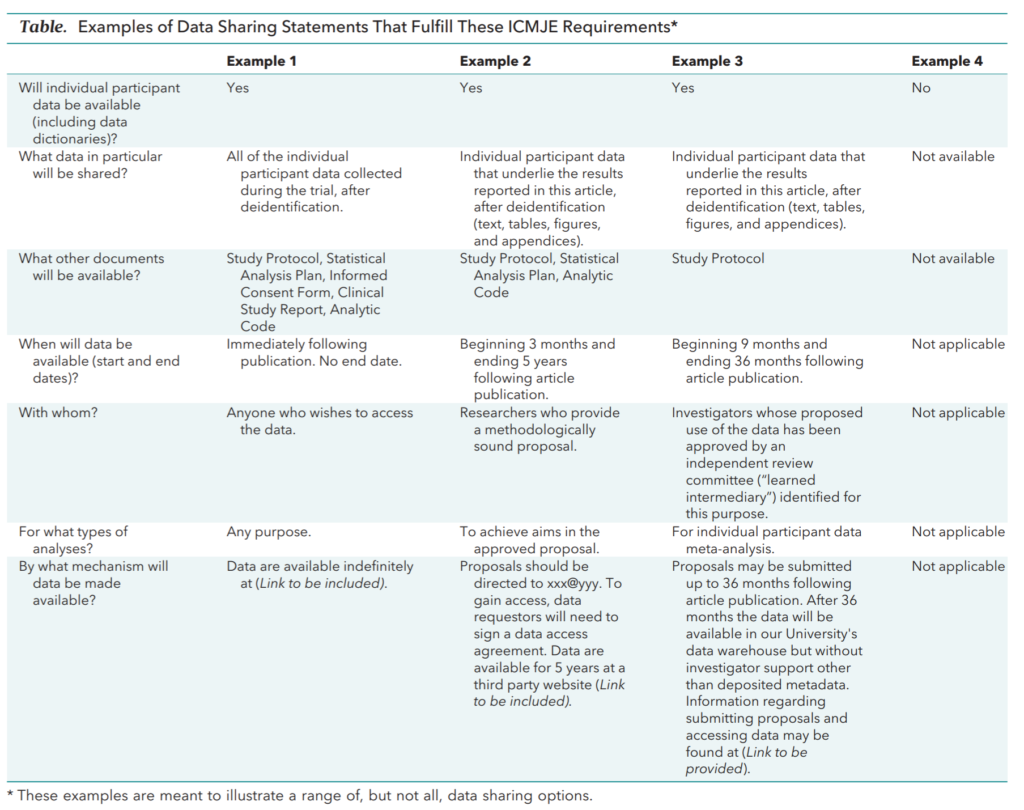

In 2014 the Institute of Medicine (IOM – now the National Academy of Medicine) convened a committee to deliver recommendations on the responsible sharing of clinical trial data. The IOM’s recommendations have led to a vigorous ongoing debate on what, how, and when data and metadata should be shared. In June 2017, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) published options in member journals for clinical trial data sharing statements. As of July 1, 2018 manuscripts submitted to ICMJE journals reporting clinical trial results must include a data sharing statement in accordance with one of the four options (see Table below).4

Access, however, is just one aspect of data sharing. The FAIR Data Principles for scientific data management propose that data should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Re-usable. Funders and journals adhering to FAIR Principles will require their authors to ensure that their data sharing plans include relevant metadata and the provision analytic code to enable researchers and machines to accurately interpret, re-use, and combine data.

The Future

The way scientific content is produced and consumed has fundamentally changed because of advancements in technology (AI in particular), and represents exciting, new opportunities for publishers. Boolean search chipped away at the walls of once siloed journal articles. Semantic enrichment, text mining, and machine learning have destroyed those walls, completely transforming journal articles into a corpus of literature-data that can be analyzed to rapidly find new insights that will speed research and development, generate new hypotheses, and challenge long held scientific beliefs and assumptions. However, before fully trumpeting the rise of the machines, I believe that human subject matter experts will always play a critical role in validating results and improving AI.

In oncology there is a wealth of N-of-1 patient case reports, from exceptional responses to new therapies to adverse events, which can and should be aggregated and analyzed. We now have the tools to bring these patient experiences together in a structured format that is conducive to deeper analysis. Imagine the insights that can be gleaned by applying machine learning to a corpus of abstracts from every oncology-related meeting and conference. What is standing in the way has more to do with people than technology.

Regarding data sharing, a word of caution to those who are calling for open data sets. More thought is needed regarding safeguards to protect data producers from plagiarism, a problem that publishers still have to police, but for which there are effective tools such as iThenticate. Publishers do not yet have a tool to analyze a data set accompanying an article to determine if it is original or downloaded from an open repository and being claimed as original. Analytical code accompanying a dataset can also be plagiarized. Patient-level data raises significant privacy concerns that cannot be ignored. In my opinion, our focus should be on accessible data instead of open data to ensure that this important resource is used for legitimate research purposes.

While the open science train has left the station, the predicted demise of traditional peer-review and the coming irrelevance of leading journal brands are premature. Quality and reputation are more important than ever in a post-truth world, where alternative facts compete with peer-reviewed research and time-tested media properties. The New York Times recently reported that it added 157,000 paid digital subscriptions in the fourth quarter of 2017, pushing subscription revenue over $1 billion for the year to 60 percent of total revenue.5 Like The New York Times for journalism, today more than ever, trusted journal brands are essential to disseminating research that readers know has been thoroughly vetted by leading experts.

The challenge we face in scientific publishing is finding the right balance between supporting the culture and ethos of open science, and ensuring that the many good and important attributes of traditional journals are not discarded. The winds of change are indeed blowing full-force on scientific publishing from many directions. Wind can be both destructive and harnessed for power and good. Let’s work together to make sure it is the latter for scientific publishing, its diverse stakeholders, and society at large.

References:

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Open Access Policy. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/How-We-Work/General-Information/Open-Access-Policy. Accessed February 9, 2018.

- Gordon G, Inglis JR, Rieger OY. Moving Circulation to Before Publication: Perspectives on Preprint Services from the Long-Established to the Newly-Created Repository Leaders. In C McAteer (Moderator), Symposium topic #1. 2018 Professional/Scholarly Publishing Annual Conference; http://psp2018conf.com/program/.February 8, 2018; Washington, DC. http://psp2018conf.com/program/. Accessed February 9, 2018.

- National Institutes of Health. Request for information (RFI): Including Preprints and Interim Research Products in NIH Applications and Reports. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-17-050.html.Accessed February 9, 2018.

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations: Clinical Trials Section 2. Data sharing. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/publishing-and-editorial-issues/clinical-trial-registration.html#two. Accessed February 9, 2018.

- Ember S. New York Times Co. Subscription Revenue Surpassed $1 Billion in 2017. New York Times. February 8, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/08/business/new-york-times-company-earnings.html. Accessed February 9, 2018.

About the author:

Mr. Sampson is Vice President and Publisher, Journals for the American Society of Clinical Oncology, where he manages a growing portfolio of journals. Prior to joining ASCO in 2013, he was an Executive Publisher in Elsevier’s health sciences journals division where he had P&L and strategic responsibility for a portfolio of more than 20 society-owned and proprietary journals. He also worked at Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in various leadership roles, including five years as Managing Director of its Asia office in Hong Kong. He was also an Executive Vice President at Conference Archives, now part of CTI Meeting Technology.

Mr. Sampson is a graduate of Cornell University and earned a Master of Business Administration degree from the Kellogg Northwestern-Hong Kong University of Science & Technology executive MBA program.

This is an insightful reflection on journal publishing then and now. There are many opportunities ahead for digital publications, which would permit sharing research data immediately and being able to synthesize the evidence across publications to analyze data more globally. Let’s discuss this more. Please post your thoughts and ideas here.