By Mark McClellan, MD, PhD, Director of the Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy and the Robert J. Margolis, MD, Professor of Business, Medicine and Policy, Duke University;

Gregory Daniel, PhD, MPH, RPh, Deputy Director and Clinical Professor, Fuqua School of Business;

Andrea Thoumi, MPP, MSc, Research Director, Global Health;

and Morgan Romine, MPA, Research Director

Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy

Introduction

Health expenditure growth around the world continues to outpace global economic growth.1 In lower-income countries, spending growth has contributed to health improvements but has not eliminated variation in quality of care and outcomes, leading to considerable variation in performance relative to spending.2,3 Those countries also face a funding gap between available public financing and needed care, threatening financial commitments toward achieving universal health coverage (UHC), even by 2030.4-6 High-income countries, which account for 4 in 5 global dollars spent on health,1 also continue to show considerable variation in spending and spending growth, alongside rising pressures on public health care spending.7 Pressure to address inefficient medical spending is rising.

Many reforms seek to respond to this pressure by promoting higher-value care. New comprehensive and integrated accountable care models and other value-based payment (VBP) approaches aim to align provider payments with care reforms that improve outcomes and value.8,9 Price transparency proposals encourage providers and consumers to choose less costly care10; health technology assessments, supported by a range of value frameworks,9 and payment reforms that link drug and device payments to measures of actual value delivered, are being used to address medical product spending.

In the Real World

All of these diverse efforts have a common need for trusted, reliable, and efficient methods for evidence of their impact and ability to sustain public confidence and improve over time. Such evidence needs to be rooted in real-world experiences — particularly real-world evidence (RWE) based on real-world data (RWD). Such evidence can enable clinical and policy decisions that reflect impacts on real-world patients and can potentially be developed at much lower cost than traditional randomized controlled trials — if such trials are feasible at all.

RWD is defined as “data relating to patient health status and/or delivery of health care routinely collected from a variety of sources.”11 RWD from electronic health records, payer claims data, and patient registries can track utilization, outcomes, and costs, providing a much more robust foundation for assessing the value that is being delivered by a specific medical product or intervention for certain patients, as well as the value of alternative care delivery pathways, particular providers, or the entirety of a health system. Gathering RWD directly from patients (deemed “patient-generated health data,” or PGHD) is increasingly feasible even in settings where complex electronic health records are not, especially for data related to outcomes that matter to and reflect the preferences of individual patients.

That said, there are significant challenges around collecting and curating high quality, fit-for-purpose data. In many countries, RWD may reside in a number of public and private sources developed for other primary uses. Within a specific type of source such as electronic health records (EHRs), there may be little to no standardization across vendors or settings, leading to interoperability barriers to developing meaningful measures at the patient level.

Fit-for-Purpose Challenges

Even with rich RWD, important observed patient outcomes may be influenced by unmeasured and unbalanced differences in patient characteristics or treatments, leading to bias. “Fit-for-purpose” RWD generally requires pairing with appropriate analytic methods to produce robust RWE on the benefits, risks, and costs of alternative medical products, practices, and care models.

Many high-profile national and international efforts are aimed at overcoming these challenges. Such RWE initiatives aim to develop data and methods that are “fit” for particular purposes — including regulatory, health technology assessment (HTA), clinical, and payment purposes. In the United States, for example, recent actions by the U.S. Congress have tasked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with developing a framework and guidance for how RWD and RWE could enhance or support its regulatory decision-making framework.

Virtual Data Systems

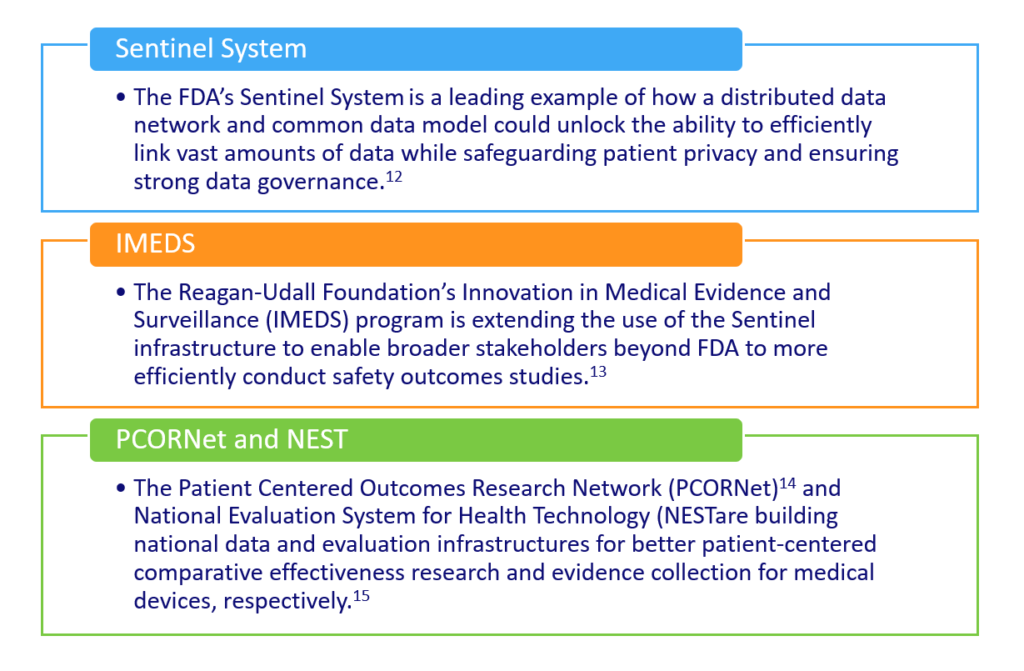

Given the pluralistic U.S. health system, U.S. initiatives have sought to advance large virtual data networks capable of collecting and using data from multiple payer organizations and sites of care. Such systems have developed governance structures and infrastructure support to develop fit-for-purpose quality assurance data and methods:

As more clinical data from EHRs are integrated into these networks, methods for gleaning critical information from full-text medical records, such as natural language processing,16 will be essential. In parallel, emerging models are improving analytic techniques for interrogating RWD data sources to better reduce bias,17 mimic randomization, and improve the credibility of the evidence produced.

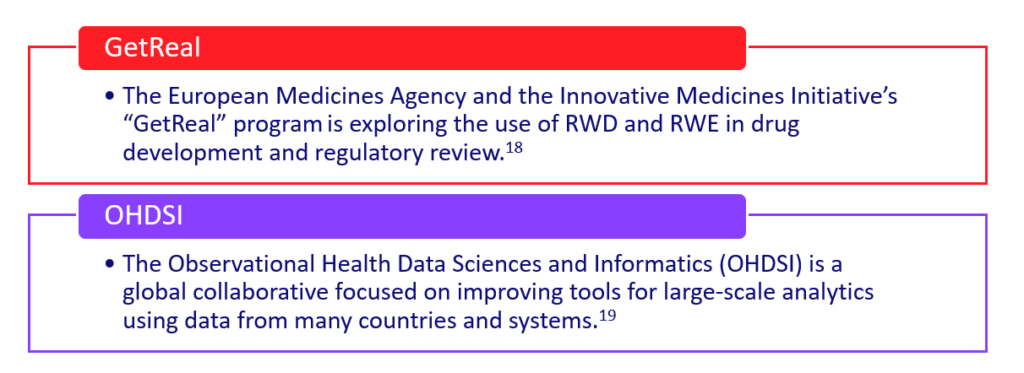

These activities are underway in many countries, and given the common challenges related to value, are increasingly drawing on international collaborations:

It is also increasingly feasible for less-developed countries to develop fit-for-purpose data and methods,20,21 and for these efforts to enable RWE development that is relevant across countries.22,23

Future Potential

Given the potential of RWE to increase the value of care, policymakers should include support for such RWD and RWE infrastructure as an integral part of health reform initiatives. A strategy should envision how data and methods can be applied across a wide range of potential uses, but should also focus on specific “use cases” that develop fit-for-purpose RWD and RWE through pilot and demonstration projects. In particular, payment reforms that are based on patient value – quality, outcomes, and resources used for prevention, chronic disease management, or patients with specialized care needs — are good opportunities for such pilots. By holding providers and product manufacturers accountable for quality and outcomes rather than volume of services or effort, they can align incentives in health care delivery with the development of patient-focused data sharing and methods for identifying steps that improve care and lower costs. Such an infrastructure can develop incrementally, starting with high-priority use cases that reflect stakeholder needs and opportunities. As it matures, such real-world evidence systems can promote the ongoing public and private sector support needed to improve access to high-value care by showing that health care spending is worth it.

References:

- World Health Organization. New Perspectives on Global Health Spending for Universal Health Coverage. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259632/WHO-HIS-HGF-HFWorkingPaper-17.10-eng.pdf;jsessionid=C2B4BA06B369C254572153D855A8AD78?sequence=1. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Leslie HH, Malata A, Ndiaye Y, et al. Effective coverage of primary care services in eight high-mortality countries BMJ Global Health 2017;2:e000424. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000424

- Jowett M, Brunal MP, Flores G, et al. World Health Organization. Health Financing Working Paper No 1. Spending targets for health: no magic number. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250048/WHO-HIS-HGF-HFWorkingPaper-16.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Dieleman JL, Sadat N, Chang AY, et al on behalf of the Global Burden of Disease Health Financing Collaborator Network. Trends in future health financing and coverage: future health spending and universal health coverage in 188 countries, 2016–40. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1783-1798. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)30697-4/fulltext

- World Health Organization. The Abuja Declaration: Ten Years On. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/Abuja10.pdf Accessed July 18, 2018.

- UHC2030. https://www.uhc2030.org/ Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Focus on Spending on Health: Latest Trends. June 2018. http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Health-Spending-Latest-Trends-Brief.pdf Accessed July 18, 2018.

- McClellan M, Udayakumar K, Thoumi A, et al. Improving Care and Lowering Costs: Evidence And Lessons From A Global Analysis Of Accountable Care Reforms. 2017; 36(11). https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0535

- Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy. Developing a Path to Value-Based Payment for Medical Products Value-Based Payment Advisory Group Kick-Off Meeting. 2017. https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/value_based_payment_background_paper_-_october_2017_final.pdf Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Brennan N. The Opacity of Transparency: The Search for a Cure to Our Health Care Woes. 2018. https://growthevidence.com/the-opacity-of-transparency-the-search-for-a-cure-to-our-health-care-woes/ Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy. A Framework for Regulatory Use of Real-World Evidence. September 13, 2017. https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/rwe_white_paper_2017.09.06.pdf Accessed July 18, 2018.

- FDA’s Sentinel Initiative- Transforming How We Monitor Product Safety. https://www.fda.gov/Safety/FDAsSentinelInitiative/default.htm Access July 18, 2018.

- Innovation in Medical Evidence Development and Surveillance. http://reaganudall.org/innovation-medical-evidence-development-and-surveillance Accessed July 18, 2018.

- PCORnet, the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network. https://pcornet.org/ Accessed July 18, 2018

- Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy. The National Evaluation System for health Technology (NEST): Priorities for Effective Early Implementation. A NEST Planning Board Report. https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/NEST%20Priorities%20for%20Effective%20Early%20Implementation%20September%202016_0.pdf Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Duke J, Chase M, Poznanski-Ring N. Natural Language Processing to Improve Identification of Peripheral Arterial Disease in Electronic Health Data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13 Suppl). http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/67/13_Supplement/2280

- Schuemie MJ, Hripcsak G, Ryan PB, et al. Empirical confidence interval calibration for population-level effect estimation studies in observational healthcare data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(11):2571-2577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708282114. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29531023

- Innovative Medicines Initiative GetReal. http://www.imi-getreal.eu/ Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics. https://www.ohdsi.org/who-we-are/ Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Wyber R, Vaillancourt S, Perry W, et al. Big data in global health: improving health in low and middle income countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2015;93:203-208. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.139022

- Regional Action through Data (RAD). http://dukeghic.org/regional-action-through-data-rad/ Accessed July 18, 2018

- Global Partnership for Sustainable Development. http://www.data4sdgs.org/ Accessed July 18, 2018

- Sun X, Tan J, Tang L, et al. Real world evidence: experience and lessons from China. The British Medical Journal. 2018; 360 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5262

About the authors:

Mark McClellan, MD, PhD, is the Robert J. Margolis Professor of Business, Medicine, and Policy, and founding Director of the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke University. Dr. McClellan is a doctor and an economist whose has addressed a wide range of strategies and policy reforms to improve health care, including payment reform to promote better outcomes and lower costs, methods for development and use of real-world evidence, and strategies for more effective biomedical innovation. Before coming to Duke, he served as a Senior Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, where he was Director of the Health Care Innovation and Value Initiatives and led the Richard Merkin Initiative on Payment Reform and Clinical Leadership. He also has a highly distinguished record in public service and academic research.

Dr. McClellan is a former administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), where he developed and implemented major reforms in health policy. These include the Medicare prescription drug benefit, Medicare and Medicaid payment reforms, the FDA’s Critical Path Initiative, and public-private initiatives to develop better information on the quality and cost of care. He has also previously served as a member of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers and senior director for health care policy at the White House, and as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Economic Policy at the Department of the Treasury. Read more at https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/mark-mcclellan-md-phd

Dr. Gregory Daniel, PhD, MPH is the Deputy Director of the Duke-Robert J. Margolis, MD Center for Health Policy and a Clinical Professor in Duke's Fuqua School of Business. Dr. Daniel directs the DC-based office of the Center and leads the Center's pharmaceutical and medical device policy portfolio, which includes developing policy and data strategies for improving development and access to innovative pharmaceutical and medical device technologies. This includes post-market evidence development to support increased value, improving regulatory science and drug development tools, optimizing biomedical innovation, and supporting drug and device value-based payment reform. Dr. Daniel is also Adjunct Associate Professor in the Division of Pharmaceutical Outcomes and Policy at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. Previously, he was Managing Director for Evidence Development & Biomedical Innovation in the Center for Health Policy and Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution and Vice President, Government and Academic Research at HealthCore (an Anthem, Inc. company). In addition to health and pharmaceutical policy, Dr. Daniel’s research expertise includes real world evidence (RWE) development utilizing electronic health data in the areas of health outcomes and pharmacoeconomics, comparative effectiveness, and drug safety and pharmacoepidemiology. Dr. Daniel received a PhD in pharmaceutical economics, policy and outcomes from the University of Arizona, as well as an MPH, MS, and BS in Pharmacy all from The Ohio State University.

Andrea Thoumi, MPP, MSc is a Research Director at Duke-Margolis focusing on health financing, comparative health systems analysis, and global health. She is responsible for directing a portfolio of projects related to evidence based healthcare delivery and payment reform and policy analysis in global settings. The work ranges from adapting international experiences with payment and care delivery reforms to the US context to identifying health financing solutions for low- and middle-income countries. Andrea collaborates with Duke global health leadership to develop partnerships and country-level engagements that facilitate health policy, regulation and financing reforms.

Prior to Duke, Andrea was a Research Associate at the Brookings Institution, where she led research on international accountable care and alternative physician payment models for oncology and diabetes. Previously, she consulted for the World Bank and the Pan American Health Organization on health equity and financial protection. Additionally, she worked as a consultant at Pricewaterhouse Coopers, conducting monitoring and evaluation for Global Fund-supported HIV/AIDS programs in Argentina and Belize. She has published research and policy analysis focused on payment and delivery reform, accountable care, diabetes and oncology. She has a secondary appointment at the Duke Global Health Innovation Center as Assistant Director, Research.

Morgan Romine MPA is a Research Director at the Duke-Robert J. Margolis, MD, Center for Health Policy in Washington, DC. He currently oversees projects related to biomedical innovation, covering a wide range of issues from drug discovery and development to regulatory review and approval to post-market evidence generation. Before joining the Duke-Margolis Center, Morgan was a Research Associate with the Brookings Institution’s Center for Health Policy and on research staff at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, Missouri.