By Kelly Saldaña, MPH, MPIA

Director of the Office of Health Systems, Bureau for Global Health, USAID

Stronger Health Systems

For many, the Ebola epidemic of 2014 served as a wake-up call for the importance of strong health systems. Strong health systems are critical not only to containing the spread of new pathogens, but also to the achievement of all global health priorities. Progress in reducing morbidity and mortality from infectious disease, poor nutrition, or lack of attention to the most vulnerable members of society is likely to cease, be reversed (e.g., reemerging infectious diseases), or even made worse (e.g., the spread of anti-microbial resistance)1 without strong health systems.

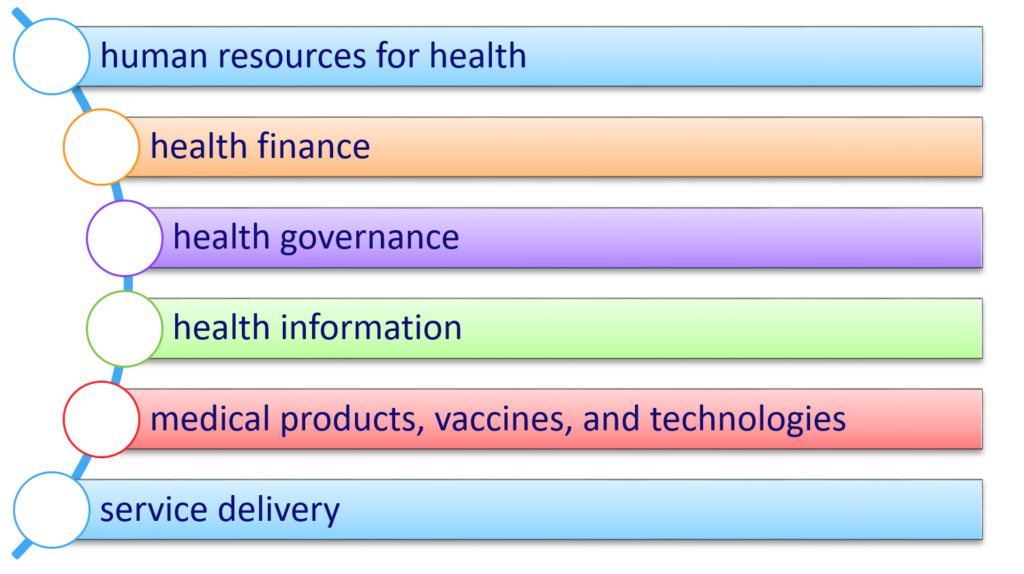

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) defines a health system as consisting of all people, institutions, resources, and activities whose primary purpose is to promote, restore, and maintain health. Often the best approaches to health systems integrate actions that impact one or more of the six internationally accepted core health systems strengthening (HSS) functions:

A well-performing health system is one that achieves sustained health outcomes through continuous improvement of these six inter-related HSS functions.

The programs and interventions that constitute health systems strengthening are often devalued or misunderstood as abstract or theoretical concepts when compared to other public health interventions that are more directly tied to the people and populations they serve. Yet health systems do impact people’s lives. HSS efforts protect families from falling into poverty due to unexpected health expenditures, guarantee that women are treated with dignity and respect when they arrive at facilities to deliver their children, and ensure that doctors and nurses have the training, equipment, supplies and medicines needed to treat the patients that come to them for help.

Defining Success

More needs to be done to mainstream health systems strengthening efforts within global health. The global community often engages in a debate between vertical and horizontal HSS programming in global health. Others have tried to bridge this division by calling for a diagonal approach that combines the two. These discussions, primarily among HSS champions, miss the point: strengthening health systems, more so than other disease or population specific health programs, relies on multidisciplinary fields of study and expertise, where differences can have more to do with the fact that practitioners don’t always “speak the same language” than real debates over achievement of results. Rather than defining success from a purely public health perspective by quantifying lives saved from interventions, progress in health systems is defined by improvements in health outcomes and also by improved governance, financial protection, or economic returns.

One way to bridge this divide is to find ways to explicitly link HSS efforts to lives saved. USAID has recently published its 4th annual Acting on the Call report,2 which shows for the first time through modeling how addressing health systems can help save 5.6 million child lives in 25 USAID priority countries over the next four years. Another way to bridge the divide is to fully incorporate HSS into overall global health programming.

For a development agency like USAID, strengthening health systems is foundational to our work and our profession. Development professionals have long understood that fostering sustainability in global health programs requires building the capacity of institutions to sustain services and enabling them to respond to changing circumstances. Therefore, strengthening health systems is integral to achievement of global health development.

Global Health Development

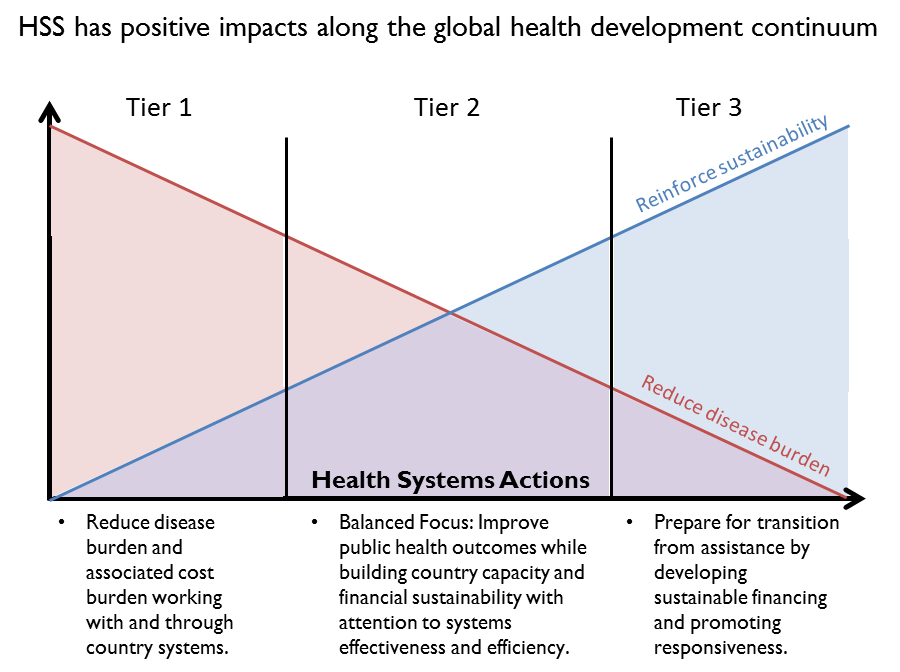

In order to better ground our work on health systems within USAID’s overall health assistance programs, we have created country typologies that recognize different tiers of health development. In the lowest tier, we understand that the global health priority is to reduce the disease burden. Reducing the disease burden has positive effects on the health system by reducing overall costs. At the other end of the spectrum we are preparing programs to transition away from donor assistance in health. However, most countries fall between these two extremes, and it is in this set of countries where we need a balanced focus between building and sustaining public health outcomes, as well as financial sustainability and country capacity. This is not to say that health systems are not important at every stage of this continuum; in fact a focus on health systems appropriate for a country’s relative stage of health development can help speed the movement along this trajectory.

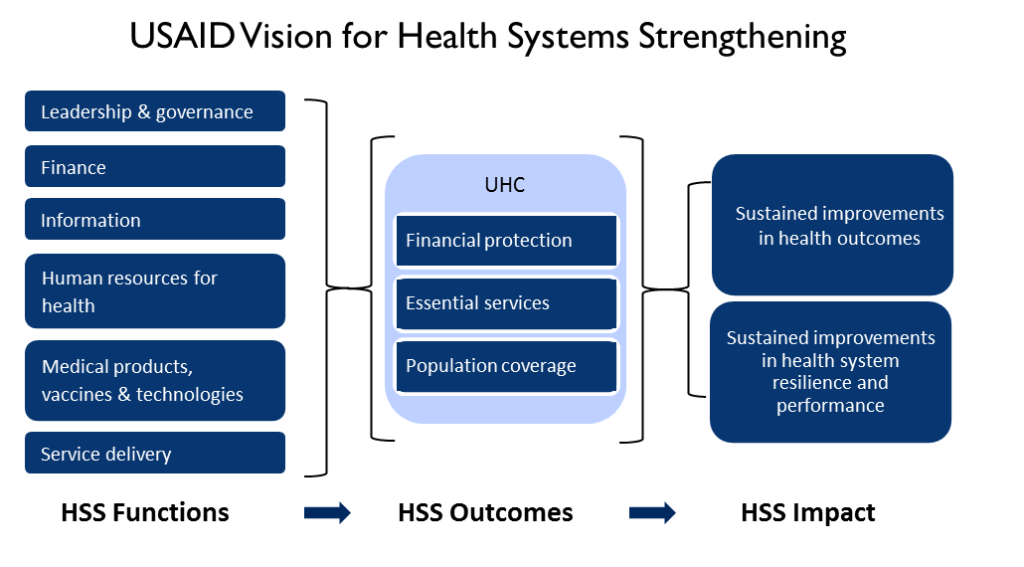

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) has been enshrined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals3 and has been widely recognized as the ultimate objective of health systems strengthening efforts.4 UHC consists of three key dimensions: financial protection, population coverage, and inclusion of a full package of services.5 The feasibility of establishing universal health coverage from a cost perspective has been demonstrated.4 However, the United States believes that UHC is progressively realized through a series of reforms and systems strengthening efforts that appreciate the roles of all stakeholders within a country health system; including government, private sector and non-profit entities. Within this progressive realization there is no consensus on how UHC is best achieved, although there are emerging suggestions that countries should first achieve the population coverage dimension so as to leave no populations behind on the pathway to UHC.5

Big Picture

Donors such as USAID work within global priorities to lower morbidity and mortality by simultaneously reducing disease burden, establishing resilient systems, and achieving universal health coverage. Doing so requires programming against a framework which helps to set priorities among these complementary objectives. We believe that by examining the relative progress of countries on each of the three dimensions of UHC, we can better articulate a program of action to establish health systems strengthening as an integral part of health development, not as an abstract or theoretical concept divorced from widespread efforts to save lives.

References:

- Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al. (Eds). Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (2nd ed.). The World Bank and Oxford University Press, Washington, DC (2006).

- Acting on the Call: Ending Preventable Child and Maternal Deaths. Washington, DC; U.S. Agency for International Development; 2017.

- Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. United Nations; 2015.

- The World Health Report – Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Health Coverage. Geneva, Switzerland: The World Health Organization; 2010.

- Vision for Health Systems Strengthening, 2015-2019. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development; 2015.

About the Author:

Kelly Saldaña is the Director of the Office of Health Systems for USAID’s Bureau for Global Health. Kelly’s career has spanned public health and international development. She has supported a wide array of health programs, especially in Latin America including the Haiti earthquake response, and more recently leading USAID's Zika response. She’s also served in a variety of roles within USAID including the Office of Health Infectious Diseases and Nutrition, Maternal and Child Health Division and the Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Well done.

Congratulations.

Outcha DARE

PhD student

University of Montréal-Health Systems